Here Is the $13 Billion Federal Case Against JPMorgan That Jamie Dimon Doesn’t Want You to See

Latest

President Barack Obama was swept into office in the wake of an unprecedented financial collapse initiated by unscrupulous banks, but his Department of Justice did precious little to actually punish the executives behind it. Obama’s federal prosecutors made almost no attempts to hold anyone criminally responsible, and they settled civil cases quietly, without the unpleasantness and embarrassing details of protracted litigation.

What would an open prosecution of bank malfeasance have looked like? In 2013, the U.S. attorney’s office for the Eastern District of California drafted an extensive civil complaint against JPMorgan Chase, describing a damning array of alleged financial fraud violations that had led to the 2008 meltdown. Rather than formally filing that complaint, though, the Obama administration used it to convince the bank to agree to pay a $13 billion settlement. After the feds and JPMorgan Chase had reached their deal, the government sought to bury the specifics of the complaint—blocking it from being disclosed in open court or through the Freedom of Information Act.

The concealment lasted until earlier this month, when Vanity Fair correspondent William D. Cohan reported the details of the complaint’s allegations, and the tortured history of the government’s—and JPMorgan CEO Jamie Dimon’s—efforts to keep them secret. The complaint had recently been unsealed in the course of a lawsuit filed by the First Amendment attorney Dan Novack. Cohan’s piece quoted from the draft complaint at length, but did not include the actual 92-page document.

Had it been filed, the complaint would have targeted JPMorgan as an institution, not individual employees. Nonetheless, the document details a litany of alleged misdeeds committed by the bank’s analysts and underwriters who had been tasked with creating, auditing, and selling mortgage-backed securities, the arcane financial instrument that devastated the global economy in 2008. Novack gave Splinter a copy, and we are publishing it here for the first time.

But even though the cat is finally out of the bag about the government’s evidence against JPMorgan Chase—four years later and under a new president—the Department of Justice still took pains to keep Jamie Dimon’s secrets. Twenty-one whole pages are completely blacked out, under an exemption to the Freedom of Information Act that protects information that may “interfere with [law] enforcement proceedings.”

It’s hard to see how the redacted material, if revealed, could interfere with any law enforcement actions. The government’s civil enforcement efforts apparently wrapped up in 2013, with the Justice Department’s announcement of the $13 billion settlement. And although that announcement noted that the agreement “does not absolve JPMorgan or its employees from facing any possible criminal charges,” most, if not all, of the events in the draft complaint occurred ten years ago, which would put them beyond the criminal statute of limitations.

The relevant law, the Financial Institutions Reform, Recover, and Enforcement Act, allows the federal government to seek civil penalties against firms for violations of certain criminal laws relating to the finance industry. Those laws usually have a statute of limitations of five years, but under FIRREA, the statute of limitations lengthens to ten years. The draft complaint repeatedly emphasizes that the Department of Justice looked at JPMorgan’s conduct “from 2005 to 2007,” which means that any such action would have to be launched in the next three months in order to stay within the statute of limitations.

Novack emphasized the absurdity of the redactions and the government’s justification for them. “For the past three years the D.O.J. has insisted that publishing the draft complaint would impede their efforts to enforce the law,” he told Splinter. “Now that the scope of their case against JPMorgan is finally public, it’s apparent that the only thing impeding the D.O.J. is itself.”

Cohan’s article provides a great deal of context for the never-filed complaint, which was drafted by the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Eastern District of California and provided to several JPMorgan executives, including current CEO Dimon, in September 2013. Two months later, the bank settled, after negotiating a provision in the agreement that forbade the Justice Department from filing the draft complaint in a public docket. A separate lawsuit, in Pennsylvania, sought to bring the complaint to light, but after a judge ordered its disclosure, JPMorgan settled the case, preventing the order from going into effect.

These efforts tracked with Dimon’s personal feelings about the settlement. As Cohan reported in 2014, the C.E.O. told an audience at Microsoft’s CEO Summit that he “had to control his rage” about the investigation and the enormous settlement, one of the largest ever agreed to by an American firm.

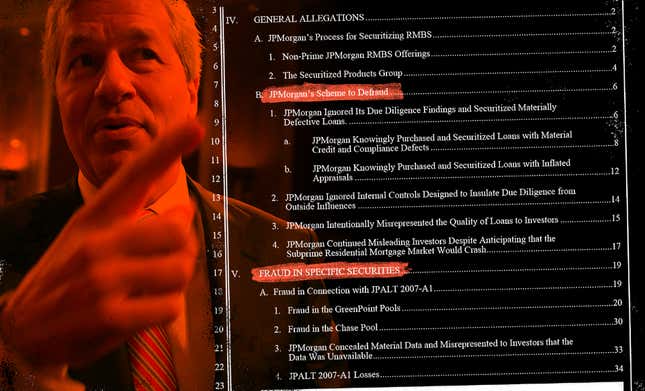

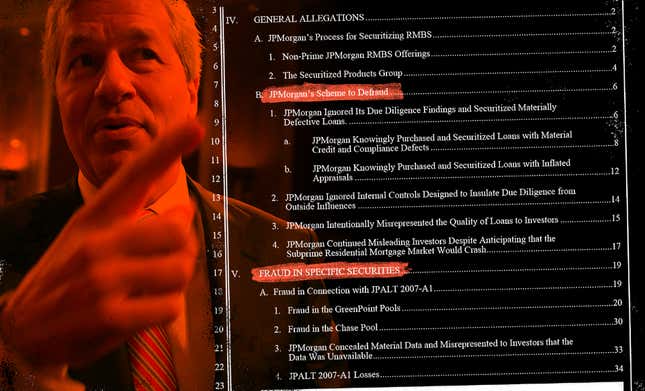

It’s not hard to see why Dimon or JPMorgan didn’t want the public to see this complaint. The introduction describes the bank as having perpetrated “a fraudulent and deceptive scheme to package and sell residential mortgage-backed securities (‘RMBS’) that Defendants knew contained a material amount of materially defective loans.” Entries in the table of contents include “JPMorgan Ignored Its Due Diligence Findings,” “JPMorgan Continued Misleading Investors,” and “JPMorgan Concealed Material Data and Misrepresented to Investors that the Data Was Unavailable.”

Even with all the redactions, there are plenty of embarrassing details. Here’s how one of the bank’s managing directors, William Buell, allegedly reacted to a disappointing audit of a tranche of sub-prime mortgages (“Event 3” loans) that had been issued by Countrywide, perhaps the most notorious lender of the financial crisis (emphasis ours):

With knowledge of the excessive Event 3 rates [i.e., the rate at which a group of mortgages failed certain underwriting standards], on March 30 and 31, 2006 Buell authorized the purchase of 5,052 loans ($887 million) from the [Countrywide mortgage] pools. Before authorizing the purchase, Buell was presented with a printout of the above-described “final” due diligence results. The printout contained a calculation based on the random sample of the estimated credit Event 3 fail rate for the pool being purchased, which was 17.82 percent. Buell scratched this out in ink, and instead notated a different calculation based on false inputs. This false calculation purported to show that the estimated Event 3 fail rate in the pool was 4.7 percent. This calculation was contrived by Buell to create the appearance that the credit Event 3 rate was within JPMorgan’s internal tolerance, when he knew it exceeded the internal tolerance by over 300 percent.

The same document suggests that Buell later developed doubts about JPMorgan’s securities business. In October 2006, the draft complaint states, “senior executives, including Buell, warned [CEO Jamie Dimon] in October 2006 that underwriting standards were deteriorating, and that [mortgage] originators were originating stated income loans with high loan-to-value ratios.” And, January 2007, Buell allegedly disseminated a memo he received from another employee identified as “Deal Manager A,” who claimed that the bank’s auditing apparatus had disintegrated.

“Deal Manager A” is most likely Alayne Fleischmann, who became a whistleblower against JPMorgan after the bank fired her in 2008. The draft complaint quotes “Deal Manager A” as telling two colleagues, “You can’t securitize these loans, because if you do, you will have to write a special disclosure, and no one will do that, because if you do, no one will buy the security.” A 2014 profile of Fleischmann, published in Rolling Stone, attributed the same quote to her.

Another JPMorgan employee, a due diligence manager named Joel Readence, allegedly manipulated a spreadsheet intended to assess the risk of mortgages that had been securitized. On the evening of October 26, 2006, the draft complaint alleges,

Readence sent [a colleague named] Kothari an email containing an inaccurate summary of the due diligence results from the [pooled mortgages], particularly the ResMAE and Fieldstone pools. Readence reported that in the ResMAE pool, the total sample for credit and compliance reviews was 30 percent and that the “[f]allout for [c]redit/[c]ompliance” was “3.30%.” For Fieldstone, he reported that total credit and compliance sample was 25 percent, and that the “[f]allout for [c]redit/[c]ompliance” was “2.67%.”

This representation was false. The fallout rate (after waivers) in the sample in the ResMAE pool, when accounting only for Event 3s was 9.59 percent. When accounting for Event 5s, the fallout rate was 12.78 percent. Similarly, in the Fieldstone pool, the fallout rate in the sample was 10.73 percent.

To obtain the lower fallout rate that Readence gave to Kothari, Readence excluded the Event 5s, and then divided the number of defective loans by the number of loans in the entire pool, not just the sample. This manipulation created the false appearance that the fallout rate in the pools was three percent or less, when in reality it exceeded ten percent (which does not include the Event 3 loans that were improperly waived into the pools). It was readily apparent from the supporting data that Readence provided in the email that he sent to Kothari at 6:09 p.m. that the fallout rate was inaccurately calculated.

As with Buell, the draft complaint indicates that Readence was occasionally uncomfortable with the bank’s actions. At one meeting with a mortgage originator, he and another due diligence manager, Robert Savery, allegedly “attempted to defend their decisions that the stated incomes in many of the loans were unreasonable and should not be waived into the pool [of mortgages].”

We were unable to identify the JPMorgan employee known as “Kothari,” who is called a “trader” in the draft complaint. Because of the broad redactions in the complaint, it is possible the available text provides an incomplete account of any particular employee’s actions.

Jennifer Lavoie, a spokesperson for JPMorgan, declined to comment to Splinter. Another spokesperson, Brian Marchiony, later wrote to us in an email: “I understand you have reached out to multiple employees—and their family members—after our company declined to comment for your story. Those individuals have asked me to reach out to you, adding that they also have no comment.”

Reached by telephone, Buell told Splinter, before hanging up, “I’m not really interested in commenting on that.” Readence did not respond to requests for comment. Savery referred our inquiries to his attorney, Andrew Genser, who did not answer our questions by press-time. The attorneys who prepared the draft complaint, including former U.S. Attorney Benjamin B. Wagner, either declined to comment or did not respond to questions. Alayne Fleischmann, the JPMorgan whistleblower, declined to comment.