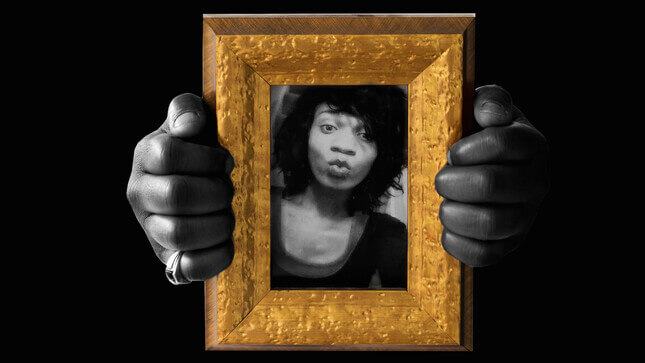

'I Am a Girl Now,' Sage Smith Wrote. Then She Went Missing.

Features

The excruciating story of how the system failed a poor, black, trans teen

On the late afternoon of November 20, 2012, just a few weeks shy of her 20th birthday, Sage Smith stepped out of the neon pink-walled apartment in Charlottesville, Virginia, she shared with two friends. After a tough and tumbling childhood, things finally seemed to be falling into place: She had moved out of her grandmother’s house, was taking classes, had just reconciled with her dad. And she had just started openly identifying as a transgender woman.

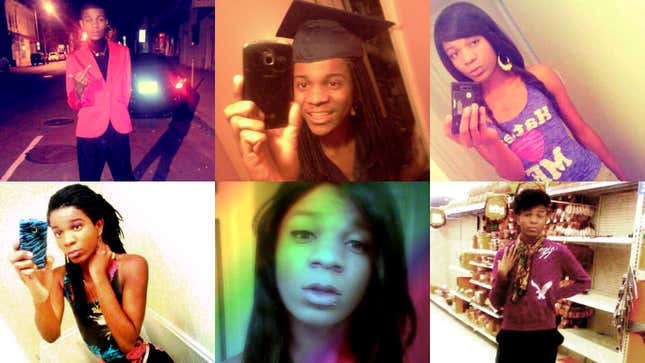

At night and on the weekends, Sage and her roommates gussied up and went out to dance at Charlottesville’s only queer club or to the strip of bars near the University of Virginia. Her friend Shakira had started taking estrogen injections and Sage wanted to start, too. Sage changed her gender on Facebook to “female.” “I am a girl now #Respect it,” she wrote to a friend on Facebook on November 9, 2012, and to a family member on November 18: “Look I am transitioning and I am your niece.”

Sage walked toward the 500 block of Main Street. She stopped to talk to a friend and told them she was going to meet a man. She didn’t come home that night, nor the next morning, nor the day after that.

Sage has been missing for more than four years and is now considered murdered, but the Charlottesville Police Department say they’re no closer to knowing what happened to her—or if they have any new information, they’re not sharing it. The prime suspect was the man she was supposed to meet, who skipped town just days after Sage’s disappearance before police could interview him in person.

After years of trying to locate him, police suddenly cleared him of suspicion in 2015, only to change their mind again. The CPD says it has aggressively pursued the case, which has been difficult, and if people have information they haven’t shared it with police. A new police chief took office last year and he promises the case is getting a fresh look—but if anything new has come to light, Sage’s friends and family certainly don’t know it.

“There’s a bigger issue there,” said Lieutenant James Mooney, the detective who’s stayed with the case the longest, and who blames the lethargic pace of the case on the fact that Sage was black and trans and poor. “Only a very small fraction of our community has taken interest in Sage.”

Sage was memorable, and stories about her abound. Like how she ended up doing a Vogue-style shoot with a UVA student on the Route 7 bus. Like how she once helped carry an old man’s groceries to his car while wearing a mini-skirt and three-inch heels. Like how every clubgoer leaned closer when Sage spoke, as if they were campers pulled to a fire, according to Jason Elliott, Mr. Pride of America. But Sage’s family and friends say, unlike those afforded to missing white girls, the investigation into her disappearance was slow, slapdash, and followed a zigzagging logic that makes little sense to anyone. And they’re in search of a better story.

The University of Virginia in Charlottesville was built by the enslaved and worships Thomas Jefferson, a pragmatic and brutal slave owner. Charlottesville’s public schools closed for five months in 1958 rather than comply with the federal order to desegregate. In the mid-1960s, a middle-class black neighborhood called Vinegar Hill was razed—under the guise of “urban renewal”—because of its proximity to downtown, which developed into a commercial corridor that would put the city on the map for education, culture, and tourism. What were once black-owned homes are now a major roadway, hotel and Staples that border a brick-paved pedestrian shopping mall.

These days, Charlottesville can claim the titles of one of the top 10 best American cities for book lovers and the “happiest city in America.” But happy for whom? This past May, a crowd, led by noted white nationalist and UVA alum Richard Spencer, gathered in Charlottesville’s Lee Park to protest the removal of a statue of the park’s namesake, chanting, “You will not replace us.”

Home values and rents are high, but the number of affordable housing units is low. The median income in Charlottesville is about $50,000 a year, yet nearly a third of its residents do not earn a wage that allows them to pay for food, clothing, housing, and transportation. Just 20% of Charlottesville’s population is black, but they make up 80% of those stopped and frisked by police. Just 6% of UVA students are black, yet people of color make up vast majority of staff in UVA’s on-campus cafes and cafeterias.

In 2011, the author of a report on poverty put it plainly: “When you look in the middle of the city of Charlottesville, you see a big orange dot and that’s where all the poor people live.”

Sage grew up in that orange dot, raised from the age of three by her grandmother, Miss Cookie, in her apartment in what was then called Garrett Square, an affordable housing complex. Miss Cookie was a dedicated parent and a prominent community figure, serving on the tenants association board and resident patrol.

When Sage was 12, and a wrought-iron fence had gone up that made the complex residents feel like prisoners, she moved Sage to a house in Charlottesville’s Fifeville neighborhood. That’s when they met Shakira Washington, who lived two doors down, and who would soon call Miss Cookie “grandma” too.

“[Sage and I] got into an altercation,” Shakira said. “Our families came out of the house and stopped it. We were together every day after that.” Shakira is trans, and was already asking her middle school teachers to use female pronouns.

One day, Sage came to Miss Cookie and said there was something she needed to confess—then asked Miss Cookie not to be mad.

“And she said, ‘Grandma, I’m gay.’ And I said, ‘You aren’t telling me anything that I don’t already know.’” They sat there hugging for a long time.

Although she often struggled in school, Sage became the first in her family to graduate high school. She took cosmetology classes, braided out of her home, and swept hair at a salon. Foster care—where she had been since Miss Cookie returned her to her mother, who was subsequently deemed unfit—paid for her to have her own apartment, so she asked Shakira and another childhood friend named Aubrey Carson if they would move in and share it with her.

Sometimes they went to parties that catered to men on the down low. They also hosted parties at the apartment on Harris Street and invited men and other friends over. They had a tight friend crew that also included Aubrey and three women named Alexis, Tiffany, and Chelsea. Sometimes they hooked up for fun, other times for money. The guys they met came from all walks of life; many of them were married. If either Sage or Shakira was going to hook up, they would text the other. One time, Shakira recalls, a UVA professor arranged for her to come over to his house in a fancy neighborhood and when the man left the room, she heard a knock on the window. It was Sage, outside in the bushes, watching her to make sure she was OK.

Shakira didn’t hold a high school diploma and getting a job without one wasn’t easy; potential employers seemed nervous when she mentioned she was trans, then didn’t call. Sage and Aubrey were harassed on the street, called slurs, once chased by a crowd. Sage’s jobs paid minimum wage, and neither Miss Cookie nor her dad, Dean, had a lot of cash to spare.

Dean had been incarcerated for several years on a drug charge when Sage was young, but now he was eager to play a bigger role in Sage’s life. He struggled to accept Sage, first as a gay man and then as a trans woman, but a Lifetime movie called Prayers for Bobby changed his mind. “Dude was like that and his family dropped him. I just felt I couldn’t do that to my child,” Dean said. “When she walked by on the street and I was at the barbershop with my boys, I would say, ‘Come here, I want you to meet my child .’”

Sage wasn’t a stranger to interpersonal trouble. Her Facebook account shows messages from March 2012 in which a friend is telling her to “watch her back,” that people on the street had it out for her because she’d contacted the wife of a man she’d hooked up with. Occasionally Sage also placed Casual Encounters ads on Craigslist, a practice Shakira didn’t approve of. This is how police believe Sage met Erik McFadden.

November 19, 2012 was a Monday, and Shakira’s 19th birthday. The friend group celebrated Shakira in style at the apartment. But then a girl came busting through the door wanting to start a fight with one of Sage’s friends over a man. The fight migrated outside. There were cars parked all the way up Sage’s street. Then car doors opened and a crowd of people tumbled out. In the fray, Sage ended up fighting with a man named Jamel Smith, an acquaintance whom Sage had seen around town. Things escalated and someone called the police.

Police responded at about 11:20pm and Jamel Smith filed a report that Sage damaged his car, but no one was arrested. Shakira said fights were not unheard of in their circle, but that something about this one felt different.

“Where did it come from? It didn’t start with Sage or me,” she said. “So it was kinda weird how it ended up on Sage.”

Later that night, Jamel Smith tweeted: “Been disrespected to the point of no return.”

After the cops left, Shakira called a couple of friends from her hometown of Norfolk, Virginia, and they came at dawn and drove her back with them to the coast. Shakira didn’t intervene on Sage’s behalf in the fight; Sage felt let down and angry.

“Her last words to me were, ‘I hate you,’” Shakira said. “We never got to make it right.”

Sage woke up late the next day and called her dad. She congratulated him on the anniversary of his getting out of jail and asked him for money to get her hair braided.

Sage’s other roommate, Aubrey Carson, said that Sage woke him up from a nap when she left and told him simply that she was off to meet a man. When Aubrey woke again around 8pm, the house was black. He called Sage’s phone but it went straight to voicemail.

“Major red flag,” Aubrey said. “Sage would charge [her] phone anywhere.” In the morning, Sage still was not back.

When the phone rang at around 9am, Shakira thought it was Sage calling to apologize. But it was Aubrey. Shakira told Aubrey to call Miss Cookie, who told Aubrey to call the police.

Miss Cookie remembers receiving this call, which detonated a bomb at the center of her life.

“The police came to the house and talked to us,” she said. “I told them what I have been saying all along: Sage would never leave her family right before Thanksgiving and not tell anyone. Somebody must have taken her.”

Aubrey called the Charlottesville Police Department on the afternoon of Wednesday, November 21. He said the officer on the line sounded calm, simply asked for Sage’s name, birthdate, and a picture.

“From the start, it seemed like they didn’t see it very seriously,” Aubrey said.

Detectives began investigating on Thursday, November 22—Thanksgiving Day. The case was originally assigned to a Detective Sergeant Marc Brake, who has not returned multiple requests for comment.

Dean and Latasha Grooms, Sage’s mother, both confirmed that it was extremely out of character for Sage’s phone to go to voicemail and for her not to have been in touch with family or friends for 36 hours. Detectives also spoke to the friend who confirmed she had seen Sage walking west on Main Street just after 6:30pm on November 20, that the two had stopped to chat, and that Sage had said she was “going to meet a man.”

“I felt they were lying to us on the whole. I did my own investigation.”

Two additional detectives were brought on board who would stay with Sage’s case for years. Lieutenant James Mooney is a big man just a few years shy of retirement with a close-shaven head who favors logo-free gray sweatshirts, belted blue jeans, and black sneakers. Detective Ronald Stayments is a second-generation cop, too, but with a slicker look—pink tie on pink shirt, handcuffs that dangle from his dress pants.

Six CPD officers conducted a “grid search” of the busy commercial corridor, checking trash cans, dumpsters, open lots, parking lots, and fields for any signs of Sage, as well as checking nearby businesses for any surveillance footage. The only camera was a traffic camera, but it only monitors, it doesn’t record.

On Friday, with Sage missing for 72 hours, Mooney got ahold of Sage’s cell phone records, which showed that Sage talked to a friend from northern Virginia for about 20 minutes on the day of her disappearance, but the last call Sage’s phone received was at 6:36pm from an unidentified number. After that call, all activity on Sage’s phone stopped.

To identify the unknown number, the detectives gave it to Sage’s family. Dean posted it to his Facebook page, and before long he received a message from an acquaintance named Yami Ortiz, a trans woman who moved in similar circles as Sage. I know that number, she said. That’s Erik McFadden.

Sage’s phone records reveal that the two had been exchanging texts and calls for several weeks before Sage’s disappearance, that they had met multiple times for sex, and that McFadden may have already given Sage some money in exchange for Sage not outing him to his girlfriend.

Years of living in Charlottesville and being stopped, sometimes seemingly at random, by CPD had left a bitter taste in Dean Smith’s mouth, and the slow start out of the gate made Dean suspicious.

“I felt they were lying to us on the whole,” Dean said. “I did my own investigation.”

Dean learned that McFadden worked at a Sherwin-Williams paint store and lived in downtown Charlottesville with his girlfriend. Dean also posted McFadden’s picture to Facebook.

“That really set us back a long way,” said Mooney, who believes that Dean posting that picture spooked McFadden into fleeing. “If we’d have had a chance to find him without his picture being out there, we might be talking to him instead of looking for him.”

At the same time, Sage’s family wonders why they as civilians had more information about the case than the police did at that point.

“All their information came from us,” Miss Cookie said, also referring to efforts undertaken by Sage’s aunt Tonita Smith, who found McFadden’s Facebook profile and, being able to access Sage’s Facebook and Twitter, began checking them for clues. “It began to feel like we were doing their job for them.”

On Saturday, November 24, after conducting a search of Sage’s neighborhood, the Charlottesville Police Department got another call about a missing person. This time, it was a young woman named Esther Ayeni. She said she had not heard from her boyfriend, Erik McFadden, who had been staying in her apartment while she was out of town for Thanksgiving. CPD detectives told Ayeni that they were actually already looking for McFadden to question him about his role in Sage’s disappearance. McFadden’s job confirmed he had not shown up to work in several days with no explanation and no warning.

The investigation seemed to have gone dark over the weekend. “I don’t think they really did enough at that time,” Shakira said. “Instead of calling people, they should have been getting people in investigating rooms and interrogating them.”

On Monday, CPD officers talked at length with Ayeni. She had finally gotten a call and emails from McFadden the previous night, Sunday, November 25—he told Ayeni he was in Washington, DC, and needed money. She told him that the police wanted to speak to him about Sage Smith and gave him contact information for the detectives.

Police entered Ayeni’s apartment looking for McFadden. He wasn’t there, but they collected McFadden’s stuff from her apartment, including his laptop computer and clothes. A receipt from CVS showed that he had been in Charlottesville until as recently as the evening of Thursday, November 22, two days after Sage went missing.

On Tuesday, November 27, with Sage missing for a week, detectives got a call from McFadden himself. Yes, McFadden explained, I was supposed to meet Sage near the Amtrak station that day, but she never showed up, and I don’t know what happened to her. He was in New York now, he told detectives. Why? “Because I’ve never been to New York before,” McFadden responded. Detective Marc Brake told McFadden that he should to return to Charlottesville. McFadden hung up.

On Wednesday, November 28, Charlottesville police officers searched the streets and wooded areas along West Main street, where Sage was last seen, and then they expanded their search to include the area around where McFadden had been living.

The next day, Esther Ayeni told police that McFadden was taking a bus to Charlottesville arriving the next evening and that he expected to be picked up by police. The police affidavit reads, “Brake reasonably assumed, based on the email communication, that McFadden would be speaking with him at that time to explain his absence from Charlottesville and his relationship with Smith.”

But that’s not how it turned out. On Friday, November 30, while coming back from a visit to a trash expert that helped them determine that the dumpsters behind McFadden’s apartment went to a landfill some 60 miles away in Henrico County, near Richmond, detectives heard again from Esther Ayeni. McFadden was going to run.

“[I]m heading out,” McFadden wrote to Ayeni in an email on November 30. “This is what happened i never did anything sexual with that guy and he was blackmailing me, he wanted me to give him money not to lie from saying we did and i did and he agreed to stop and then the next time he hit me up for money i said no…we did meet up but he had alot of enemies me and him were walking and some people sowed up and i kept walking not looking back.”

In other words, McFadden did in fact meet up with Sage. Police obtained warrants for McFadden’s computer, email accounts, cell phone apps, Twitter, and bank records. Another email to Ayeni in May of 2013 from an untraceable email address is the last anyone has heard from Erik McFadden.

That December, police made two more efforts to find Sage. On the first, Charlottesville police, in conjunction with officers from the Virginia Department of Emergency Management and cadaver-sniffing dogs from the Virginia Search and Rescue Dog Association again searched the areas around Main Street and McFadden’s house as well as nearby railroad tracks and near a deep sediment pond. A dog made a “slight indication” that they picked up Smith’s scent.

A dive team was called in to search the pond but nothing turned up. The final attempt was a large-scale search of that Henrico landfill that involved Charlottesville police officers as well as officers from Henrico County, forensic and hazmat personnel and a retired Special Agent specializing in landfill searches. But they found nothing.

Over the past four years, Sage’s case has stayed “under active investigation.” In January of 2013, detectives met with agents from the FBI and U.S. Marshals Service to see if they might be able to consult or provide assistance. In May of 2013, they got in touch with the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children. Later that month, dental records for Sage were obtained and placed into a national registry. A few tips came in that Sage might be living in the Tidewater area or in the Carolinas. They went nowhere.

On September 13, 2014, a white University of Virginia sophomore named Hannah Graham went missing from Charlottesville’s Downtown Mall. Within 24 hours, the Virginia State Police had taken over the case.

By September 15, nearly every law enforcement office in central Virginia knew Graham’s name and dozens of officers were searching. Then the FBI came on board, as well as the Albemarle County Sheriff’s Office, the Blue Ridge Mountain Search Group, and the Virginia Department of Emergency Management Services. More than 5,000 tips flooded in, necessitating a separate Hannah Graham tip line. Police announced a $50,000 reward for information, $10,000 of which came from the City of Charlottesville itself (the reward pool would later total $100,000). A massive volunteer search drew more than 1,000 participants from all over the state.

In the early hours and days of Hannah Graham’s disappearance, Charlottesville Police Chief Tim Longo gave several press conferences during which he shook his fist, banged the lectern, and wiped away tears.

Communications Officer Captain Gary Pleasants was sending 146 members of the international press updates more than once per day.Detective Mooney was also the lead detective on Graham’s abduction case. Law enforcement officers from all over the country were calling offering help—did Mooney need trucks? Helicopters? A drone? The CPD declined to disclose the total amount spent on the search, but it has been called the most extensive and intensive in Virginia state history. “Ungodly amounts of overtime dollars,” Mooney said.

The suspect in Hannah Graham’s case fled as well, triggering a national manhunt that located the fugitive in Texas in three days. Hannah’s remains were found after 36 days and the suspect pleaded guilty in spring of 2016. He will spend the rest of his life in jail.

“How do you think I feel?” Dean Smith wants to know. “I watched the helicopters come right up and over the field there behind my house. They didn’t do that for my child.”

Hundreds of thousands of people are reported missing each year, but most of them are found. Key factors distinguish these ordinary missing from the truly gone, and it falls to law enforcement, who have finite time and resources to tell the difference, and quickly. Every expert says that the the choices law enforcement make in the first 72 hours determine the outcome. In Hannah’s case, every choice was made correctly. In Sage’s, many of them were not.

The Virginia Department of Criminal Justice Services has clear protocol as of 2015 for high-risk missing persons cases (though no such document existed in 2012; when called for comment the CPD declined to do so). The protocol includes making requests for search and rescue and other external support “in the early hours of the investigation.”

Yet the detectives did not make requests for substantive external support in this case until December 1, 2012, 11 days after Sage went missing. Detective Mooney said the Virginia State Police and the U.S. Marshals were consulted, and that the FBI offered technical assistance to find McFadden. When contacted this February, the first two agencies said they never had any agents working on Sage’s case nor are they actively assisting on it now.

Protocol also advises police officers to contact local government and trash companies to request a delay in trash collection near where the subject was last seen or might have been abducted. CPD did not request any such delays. Finally, protocol advises detectives to get consent or obtain search warrants for emails, chats, and “other online communications” for clues relevant to the disappearance and to communicate frequently and openly with the victim’s family.

Police did file for a warrant to search the email files associated with Sage’s phone as well as the laptop they seized from McFadden’s apartment—but not until March 11, 2013, nearly four months after Sage’s disappearance. Miss Cookie states that she had to call and leave messages for several days, even during the first week of the investigation, in order to receive a return phone call from lead CPD detective Marc Brake.

Aubrey Carson, who called about Sage’s disappearance, was not contacted until “three or four days, maybe longer” after Sage went missing. Aubrey was staying with his grandmother 20 minutes north of town. Detectives asked Aubrey to come down to the police station. Aubrey agreed, but because he didn’t have a car, he asked to be picked up at his grandmother’s home. The detective agreed. But no officers ever showed. Aubrey was not interviewed for nearly two more weeks.

“When Hannah went missing, people were beating down the door to help. In Sage’s case, it was like pulling teeth.”

When interviewed in January of 2016 in her home on Chincoteague Island, Virginia, Shakira said detectives had never talked to her beyond a short factual phone call. Mooney said he and Stayments had been meaning to go up to see her but that his desk duty, which he had for most of 2015 due to a knee injury, had prevented it.

A final point of misstep was police communication with the public. On November 28, with Sage missing for eight days and detectives searching the areas around McFadden’s apartment, CPD Lieutenant Ronnie Roberts called the first press conference about Sage’s case.

“It’s not a criminal case,” the lieutenant told the gathered reporters, nearly all local or regional. “We have nothing at this point in time that indicates it being a criminal case, which makes it difficult to get warrants and things of that sort, because you have to have a criminal case to go in that direction.”

“I don’t know why he said that,” Mooney said recently. “He was our public information officer. He should have asked for the public’s help.”

Mooney said the case was clearly criminal since November 30 when McFadden sent the email to his girlfriend admitting to meeting with Sage. “At that point, this obviously wasn’t a missing persons case anymore—something had happened,” Mooney said. In the police affidavit for a warrant to search McFadden’s computer, Lieutenant Mooney wrote, “These facts when considered together present probable cause to believe that [Sage] Smith has been abducted, is either being held against [her] own will or has met with harm.” The search warrant was granted; the charge was criminal abduction.

But Lt. Roberts must have not gotten the memo. An NBC29 article from December 1 read, “At this point, police do not suspect foul play.” And on December 7, Roberts responded to Sage’s family’s public pleas that the department request help from the Virginia State Police or the FBI by saying that the City would refrain from seeking investigative assistance unless it were deemed necessary, which in this case, he said, it was not. Another article from December 2014 in the C-VILLE Weekly, Mooney said police are still treating Smith’s disappearance as a missing persons case, not a criminal investigation.

“I don’t know why I would have said that,” Mooney said. “Maybe it was for a strategy.”

Leading up to the third anniversary of Sage’s disappearance, in 2015, the police department held a press conference to announce that the CPD no longer believed McFadden is responsible for abducting Sage.

“He didn’t have the means to get rid of anybody,” Mooney said. “He didn’t have a car, he was living in a suite with other people, it’s very unlikely that he would have done that. And he stayed in town until his picture popped up on Facebook. He was here for almost three days after [Sage] went missing.”

“The frustrating part is that instead of helping us find Sage, people want to argue about gender issues and things like that. I don’t think it should matter.”

It seems then that all of the information that led investigators to believe Sage had been abducted and that McFadden was responsible, Mooney acknowledged, was available to police investigators within the first days of Sage’s investigation. Yet the public was allowed to believe otherwise.

“What happened?” Miss Cookie asked. “How did this go so wrong?”

Mooney doesn’t see it that way. When asked what the protocol is for a missing person, Mooney answered, “There’s no standard there. The facts kind of dictate your actions.”

Detective Stayments agreed, adding that the CPD receives a missing persons case nearly every other day. Charlottesville is a hub for Virginia youth from around the state in the midst of juvenile detention proceedings.

“Juveniles run away from these community detention homes all the time,” Stayments said. “A lot of times those kids show up within a few hours, they just wanted to leave the home for a while and do whatever they want to do and then come back.”

Many of these cases involve young people who are black and poor. Is it possible that since Sage is also black and poor, detectives assumed Sage was one of these itinerant youths? Mooney says no. But Natalie Wilson, co-founder of the Maryland-based Black and Missing Foundation, who worked with the Smith family, said police more often classify minority children as runaways rather than victims of crimes, and that the reverse is true for white children.

Aubrey said that when detectives finally interviewed him, they brought up a time the year prior where Sage and Aubrey had left Charlottesville for several days to go to the beach, but Aubrey said they had been clear with their family where they went. Aubrey said that police asked, “Well, wouldn’t Sage run away again if she had done it before?”

Furthermore, the detectives had a history with the Smith family. Detective Stayments was the officer who responded to the call about the fight the night before Sage disappeared and took Jamel Smith’s statement against Sage.

“I had run-ins with Detective Mooney because I wasn’t no angel in the streets,” Dean Smith said.

“Yeah, I know Dean,” Mooney confirmed.

The Charlottesville Police Department is no stranger to racial controversy. From 2003 to 2004, as part of a rape investigation, Mooney and other officers stopped black men on the street, showed up to their homes and workplaces, and demanded cheek swabs; all told, officers collected swabs from 190 black men. There was widespread outrage and one man filed a 2004 lawsuit against the CPD that specifically named Detective Mooney for assault and battery, and racial discrimination.

Then there are the facts that Sage is trans and had moved within the queer community. In official police documents, the person the police are looking for has always been “Dashad Laquinn Smith,” Sage’s birth name. Sometimes “Sage Smith” is added in quotes or referred to as an alias. Mooney and Stayments have said they understand what it means to be trans, yet in all email and phone correspondence with Fusion they have used “he” and “his” as well as Dashad. In police affidavits and statements to media, Mooney repeatedly refers to the fact that McFadden had gay sex as his “alternative lifestyle.”

One night in the winter of 2013, Sage’s father Dean and his partner Latasha Gardner say they got a call from Detective Stayments. Stayments went to Charlottesville High School with Dean and the two families knew each other a little bit.

“He sat right there on that couch,” Dean said. “He dropped his handcuffs on that table. He said, ‘We dropped the ball. We weren’t prepared for something like this.’”

Miss Cookie said she also received a home visit from Stayments around the same time. “He said his conscience was eating away at him,” she remembered. “And he just couldn’t sit by.”

Detective Stayments doesn’t deny that he has been to both Miss Cookie and Dean’s homes on several occasions. “My heart went out to them and I did talk to them,” Stayments said, “but I never said anything that would imply that our officers didn’t do everything they possibly could have done in this case.”

“I can tell you my detectives bust their ass on every case they get,” Mooney said. “The frustrating part is that instead of helping us find Sage, people want to argue about gender issues and things like that. I don’t think it should matter.”

Still, Mooney admits that the police could only do so much in a city that was more inclined to sympathize with victims that look like them—and that sympathy controls resources and response.

“When Hannah went missing, people were beating down the door to help,” he said. “In [Sage’s] case when you ask for help it wasn’t an easy process. It was like pulling teeth.”

Police Captain Gary Pleasants said that the Hannah Graham case and the Sage Smith case are different because in Hannah’s case, she and Matthew were seen together, plus Matthew had access to a car but Erik McFadden didn’t. Still, it’s hard not to compare the demeanor of Charlottesville’s Police Chief Tim Longo while talking about Hannah versus Sage.

When asked by a local activist if he had ever cried for Sage, Chief Longo admitted he had not. By explanation, Longo told a reporter from the local alt-weekly, “I think, I felt as if I were in the shoes of [Hannah’s] parents, as a dad having a 15-year-old girl who is growing up too quickly,” he said. “I’m a human being and I can’t always control how I react to things.”

In early 2013, the Smith family requested an interview with Chief Longo because they felt their concerns weren’t being taken seriously by detectives. But they say it was nine months before Longo consented to sit down for a face-to-face meeting.

“He just told us, ‘I’m sorry but I don’t think there’s going to be a good outcome,’” Miss Cookie recalled.

Detective Mooney and now-former Chief Longo have both expressed that they felt some hostility and anti-police sentiment coming from the Smith family in a way that hampered communications.

“Miss Cookie very quickly came out publicly and blasted the police department before she met with anybody,” Mooney said. “That didn’t sit right with a lot of people.” Mooney specifically recalled an incident at a vigil for Sage held at Miss Cookie’s house in which those congregated chanted “Fuck the police.”

Another point of contended inequality is the difference in money spent on the two cases. All told, the police department spent $127,000 to find Sage Smith, the lion’s share of which was spent on the fruitless Henrico County landfill search.

And then there is the reward money that the city of Charlottesville gave in Hannah’s case within a week of her disappearance. By comparison, in Sage’s case, on December 18, nearly a month after Sage went missing, an anonymous donor gave $10,000. The city contributed nothing until Miss Cookie inquired about the discrepancy. Charlottesville City Council member Kristin Szakos responded that the $10,000 had indeed come from the city.

This wasn’t true. The CPD, who gave that information to Szakos, claim they genuinely thought the money for Sage had come from them. But as it turns out, it hadn’t. Confronted with their mistake in 2012 and their mistaken public statement in 2014, the City of Charlottesville rectified the error and donated $10,000 to Sage’s reward, two years after Sage went missing, bringing the total reward to $20,000.

In November 2015, Mooney and Stayments took to the streets to distribute flyers to local businesses and along the corridor where Sage was last seen. Some of the businesses flat-out refused to let the detectives hang the posters, Mooney recalled. One reluctant business owner told Mooney, by way of explanation, “It’s kind of a downer, isn’t it?”

“I know some of what the family’s experiencing because I see it, too. Racial problems. Gender issues,” Mooney said.

Fellow queer people of color in Virginia and nationwide have stepped forward to raise awareness for Sage at rallies, conferences, and city council meetings as well as through fundraising campaigns—groups like Black Action Now, the Lavender Kitchen Sink Collective, and the Richmond chapter of Southerners On New Ground. CeCe McDonald visited Charlottesville to do an event in honor of Sage. “Just know that it could have been you,” she said in a video from the event. “Put yourself in the shoes of this family. Think about what you would do if it was your child…We are all equal, we are all valid, and we need to show support and get active.”

Since Sage went missing, Miss Cookie’s body has simply shut down. Her heart is quite literally broken—she’s been diagnosed with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and during her triple bypass surgery, doctors had to take a vein from her leg and put it in her chest to keep her alive. She’s also struggled with breast cancer and congestive heart failure. Oxygen tanks line the kitchen walls of her apartment. Sitting outside on the sidewalk in a wheelchair, neighbors smile and greet her. (Her health problems are ongoing; Miss Cookie wasn’t able to participate in a second photo shoot because of emergency health care.)

One question that still plagues Miss Cookie is why the detectives didn’t get a warrant for McFadden’s arrest. Such warrants would have allowed CPD to track him across state lines and get access to other national resources, as was done in Hannah Graham’s case.

“I probably could have gone out and gotten a warrant for Erik McFadden but we didn’t have enough to prosecute him,” Mooney said. “Down the line, a judge could determine that we didn’t have probable cause and then throw out the results of a search or interrogation. I didn’t want to jeopardize the case.”

For better or worse, law enforcement spent the early days of Sage’s disappearance investigating McFadden, and only McFadden.

But Sage’s father wishes other leads had been explored too. “In my gut, it’s the friends,” he said. “I think [Aubrey] had something to do with it. They all disappeared.” (Aubrey denies this, claiming he was home.)

When Dean went over to Sage’s apartment on Wednesday, all of Sage’s wigs were gone. He believes Aubrey took many of them, though Aubrey vehemently denies that, too. Another of Sage’s friends was wearing a locket on a chain that had belonged to Sage. When asked, the friend said, “My boyfriend gave it to me.”

Aubrey was caught on video on Wednesday, November 21, at a gas station using Sage’s EBT card.

“Your friend is missing and you’re using her food stamp card?” Dean Smith said in disbelief. “No.”

Was Aubrey indeed home at the time of Sage’s disappearance? Maybe, but no one can verify it. Aubrey’s phone was indeed pinging off a cell tower near the Harris Street apartment, but Mooney said in a small town like Charlottesville where cell towers are far apart this isn’t necessarily conclusive.

As a possible motive, Dean suggests jealousy. “[Sage] had her own crib, she had family support, she didn’t want for anything. To see your friend thriving and you’re not. When they went out, Sage would get all the attention.”

“What makes one life more valuable than another? That’s how it makes our family feel, that we don’t matter.”

Shakira reiterates her concerns about the fight and Jamel Smith. After Jamel Smith tweeted that he’d been “disrespected” on November 19th, the night before Sage went missing, he didn’t post anything for a month, even though he had been tweeting almost daily up to that point. Later, on May 11, 2013, he retweeted, “I can’t stand a nigga that wants to be a woman. I want a man who’s a man, not a man who’s a woman.”

“It’s a scenario we considered,” said Mooney, who acknowledges that Jamel Smith didn’t have an alibi. Where is Jamel Smith now?

“Is it Richmond or is it Florida? I can’t remember,” Mooney said. “One of them’s in Florida. But without evidence, we couldn’t really investigate.”

Charlottesville has a new police chief now. His name is Al Thomas Jr., and he’s the first black man to ever hold the position in Charlottesville. Chief Thomas met with the Smith family in August 2016, and initially seemed attentive to their concerns.

But future inquiries from Miss Cookie went unanswered. Then, in late March, Miss Cookie read online that the case had been reclassified as a homicide. (Neither Chief Thomas nor the departmental spokesperson could comment on the reasoning behind this change.) A petition to Chief Thomas was started to urge him to ensure the CPD continues to aggressively investigate Sage’s case and communicate openly with Miss Cookie. When that failed, Miss Cookie and her community supporters staged a protest outside CPD headquarters.

In mid-April, Miss Cookie finally sat down with the new police leadership team. They informed Miss Cookie that Sage’s case had been assigned to a new detective, Regine Wright-Settle, that she was working solely on Sage’s case and had undergone training in homicide and cold cases to prepare for it. She is also approaching the case with new eyes, re-interviewing witnesses rather than relying on Mooney and Stayments’ notes.

When Miss Cookie asked why it had taken four years for Sage’s case to be classified as a homicide, the new investigation team blamed the old, saying they could not speak to frustrations with actions in the past nor disclose details of what specifically the new detective was doing due to the case being an ongoing criminal investigation. CPD leadership agreed that it was suspicious that Erik McFadden continues to be missing and that his family in Maryland has not filed a missing person’s report.

“So y’all gonna bring the FBI in or what?” Miss Cookie asked. “What is being done to find this man?”

A captain told her that Sage’s case now being classified as a homicide gives them the ability to bring in the FBI “if and when” they are needed.

But the family and police leadership still struggle to work together. Lieutenant Joseph Hatter asserted that it was necessary for CPD to continue to refer to Sage by her birth name in order to get the best information from the public, and Chief Thomas said that in the eyes of science, the department was still looking for a male (Sage’s birth mother agrees). Plans for the Charlottesville Police Department to undergo transgender sensitivity training may be in the works, but nothing is definitive yet.

At a recent vigil, Miss Cookie appeared in a wheelchair, wearing a huge faux fur coat, a loan from a supporter to block out the freezing wind in Lee Park.

“We need some closure,” she said in front of the small crowd, who stand holding balloons marbled pink and purple. “What makes one life more valuable than another? That’s how it makes our family feel, that we don’t matter.”

Dean Smith was there, too. His face and beard were buried into the collar of his North Face jacket, stamping his feet to shake off the cold. His voice is clear and loud. “I miss my child,” he said. “I’ll be sitting at home eating and I stop eating and think, is my child eating? I don’t sleep. Never cut my phone off. I haven’t changed my number. I usually change it every couple of years. Sage was taken from me just as we were getting to know each other. I’ll never get to truly know my child.”

The CUE Center for Missing Persons was there to support the family. They even had a bench made in Sage’s honor. Miss Cookie asked the City if she could place the bench in a city park and plant a tree in Sage’s memory.

“They told us, ‘Sure,’” Miss Cookie said, “but that it would cost us $1,000.”

This story was edited by Nona Willis Aronowitz, fact-checked by Jessica Corbett, and copy-edited by Nara Shin. Original photos by Keith Alan Sprouse.