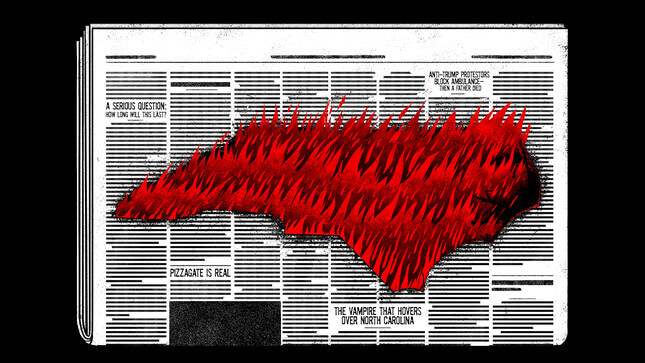

Losing the Lede to North Carolina's Far Right

State Of The Nation

Illustration: Jim Cooke

The South is not misunderstood. It never has been.

Throughout its history, the region has been covered the same way the rest of the nation has been—by people with an agenda, aiming at one end or the other. For all the stomping any Southerner can rightfully carry on with concerning how they’re portrayed in the media, the context for that coverage was informed and shaped by, and reflective of, home-grown assholes.

As Southern media has expanded and shriveled, there have been constants, which remain among the dwindling pages of today’s remaining daily print editions. The parties around them have shifted their focus, but the bone-deep racist and sexist tendencies that we so often like to pat ourselves on the back for eradicating have survived, and persist not despite the light shed on them, but because of who directs that light. The stories of people like Josephus Daniels and Jesse Helms aren’t, in the end, about them; they’re simply figures whose resonance allows people with the time to trace through history and understand how easily otherwise intelligent, good-hearted people can have their worst tendencies twisted against them. The people who filled the newspapers, whose voices carried on the radio waves and then through the television screen and now on your timelines, have not changed in anything but their form. Their essence is the same, shifting just enough with the times so as to mask their ongoing service to baseline intents of American conservatism, the ones that Reasonable Republicans and short-memoried Democrats would have you believe are trapped in some sort of imaginary past.

The history you believe to be history is rarely confined to the past. Decisions made decades, even centuries, ago continue to reap rewards for the groups that were once allowed to make those decisions. Even then, those groups have been whittled down and down until just a select few atop the industries and political machines that shape our modern country take in nearly all of those rewards, leaving those who have remained in the thrall of the Old South fuming at both their lack of material gain and the rise in complaints from groups kept from the beautiful fiction that is the American Dream.

Covering the South and its history, as C. Vann Woodward put it, is a burden. But it is not a burden on the writer. It is a burden borne by the subject, a burden that continues to latch its anchor to the neck of the wonderful region I call home to this day.

When The “Tar Heel Editor” Put Party Over Policy

One time, and one time only, Dallas Woodhouse, the current executive director of the North Carolina GOP and a person you should never believe at first pass, wasn’t wrong. He was being facetious, yes, but he was not wrong.

A little over a century ago, an outright and overtly racist Democratic Party snatched back the Tar Heel State from a multiracial legislature by means of an all-out, statewide white supremacy campaign, one that can be best described as one of the most effective #FakeNews campaigns in state history. The party they usurped—literally usurped—was an admirable bunch, even by modern standards.

That party was referred to as the Fusionists, and it had grown out of the post-Civil War populist movement to create a multiracial coalition of rural Populists (the state’s farming community) and Republicans (the state’s mountain and black communities). Up to the turn of the 20th century—and really up until the 1970s, give or take—North Carolina was a state chiefly composed of small, poor farming communities and mill towns; these places were rural and surpassingly insular. The state had no major cities, unless you counted the still-nascent Raleigh.

In the time directly following the end of the Civil War (a war that cost North Carolina more men than any of its other Southern rebel cohorts, a wound made more hurtful by the fact that the citizens initially voted against joining the war) and the period known to most as Reconstruction, the North Carolina legislature landed in the hands of the Democratic Party, though not firmly. From 1880 to 1896, the Democrats failed to ever secure more than 54% of the gubernatorial vote.

The Democratic Party of the time was an elitist institution of and for old Confederate generals who had gone back to being industry leaders in the media, railroad, textile, and banking sectors. As such, their policies showed little concern for the state’s working class, which was most everyone. But as times grew tough on farmers, with loans for necessary equipment and crops being reserved for those with the cash on hand, the long roads between these various poor farming communities started to shrink. That’s when, with a little push, they decided to take real political action.

Texan farmers were experiencing the same problems as their friends in the Tar Heel State. So, they began fighting for a seat at the table starting in the 1880s, starting a movement known as the Pitchfork Rebellion, one that found a home in North Carolina in the form of the Farmer’s Alliance.

At the head of the Alliance was Leonidas Polk, a farmer born in Anson County, North Carolina (not to be confused with the North Carolina Confederate general of the same name.) Polk was a newspaper man in the town he founded after the Civil War, running his own paper, The Ansonian before being appointed as the state’s first-ever Commissioner of Agriculture in 1877. But Polk grew dissatisfied by the state government’s failure to listen to the needs of farming families and so, three years later, he resigned in anger and started a second paper, The Progressive Farmer. There, he wrote editorials calling for all the overhaul measures needed—a graduated income tax on the wealthy, a well-funded public education system, and the organization of farmers to stand against the banks.

When the Alliance caught fire in Texas and spread through the South, Polk stood out in front of the North Carolina chapter and soon the entire organization, leading 100,000 North Carolina farmers to contribute to the cause. Come 1889, Polk was elected president, a spot he would hold for two more election cycles. As the leader, he called for the federal subsidization of crops so that farmers would not have to worry about having their land and property seized by the banks if they had a down year.

With one of their own at the helm, the Alliance spread rapidly throughout North Carolina. Farmers who had previously never given much thought to participating in the political process were suddenly awakened to the potential power they could harness if they banded together. After a couple of years of solid growth, there came a call to take the movement to Washington D.C. While some in the Alliance were content to continue their work on a local level and leave the national politics aside, a vocal section of the group set it sights on a national effort, one that would have a voice in the federal government.

In response to this growing rift, the more radical members of the Alliance split off from their Democratic roots to form the Populist Party. Understanding the need for a numerical advantage, the Populists combined party with the African-American Republican voters, forming the short-lived but influential Fusionist Party. Although they maintained separate organizations, they agreed it was in their best interest to fold their parties together so as not to split the ticket and hand the state to the Democrats.

Such political and labor organizing in rural farming communities was rare prior to the Civil War, but the Fusionists were a party bred of a response to an economic, and thus personal, survival instinct. At the time, the eastern North Carolina rural farming economy was propped upon one pillar: tobacco. Other crops, such as wheat, cotton, and corn, were regularly grown and seen in fields across the state; as the old saying goes, though, “Corn feeds the nation, but tobacco pays the bills.”

With but one main cash crop for small farmers to rely on for the bulk of their annual income, techniques such as crop rotation weren’t used as intensively as they should have been; combined with the fact that there were simply too many farmers attempting to work too little land, the soil was prevented from ever fully regaining the lost nutrients that each season’s haul would sap from the earth. The other critical issue had to do with the economic model that the majority of North Carolina’s small farms relied on—tenant farming. The majority of farmers could not produce the necessary credit to make themselves a legitimate force when dealing with the banks or selling their crops to the large-quantity buyers like the Duke family, which would go on to form the American Tobacco company empire and dominate the state’s field workers.

The Fusionists played to growing popular dissatisfaction with the state’s self-interested wealthy class of Democrats and represented the have-nots of the time: the small family farmer, the newly freed black voter, the mill worker, and anyone else who rejected the Democratic oligarchy that had risen from the ashes of Reconstruction to snuff out any actual progress toward a more equal society. They relocated power from the central hub of the General Assembly and provided local governments with increasingly democratic voting power by requiring appointed election officials to be equally represented by all parties.

During their brief reign, 1,000 black citizens were elected or appointed to office across the state. Daniel Russell was elected governor and Marion Butler, the Farmer’s Alliance leader and publisher of the newspaper the Caucasian, claimed a U.S. Senate seat. The party also focused its efforts on filling local governments with black and working-class politicians. These were real, historic victories. But the Fusionists and Populists were struggling to produce financial power at the national stage by 1898. It was through no fault of their own, but by then it was far too late; the window had snapped shut. Or rather, it had been slammed.

On the back of a hate-filled news campaign, their demise came, and the reverberations can still be felt in the state’s politics and elsewhere.

There are media titans, and then there is Josephus Daniels.

In this series’ installment on Jesse Helms, the focus, as it related to the Tar Heel state’s newspapers, rested on Helm’s relationship with Jonathan Daniels, the editor and owner of the Raleigh News & Observer. While no liberal hero even by the standards of his time, Jonathan possessed a progressive streak relative to the other powerful white men of his time when it concerned the issue of race and Jim Crow policies, a streak Helms played up his entire career as that of a privileged son who was out-of-touch with the common-folk. Jonathan’s father did not share these same views.

Daniels grew up in the state’s Second Congressional District, a black district; as a child, he saw firsthand the bi-racial working class voting bloc that the Fusionist party of the 1890s sought to achieve. Daniels, a lifelong Methodist and avowed prohibitionist—he believed that allowing black people to drink would lead to an increase in assaults on white women—wanted no part of it. Over the rest of his life, he used the power of his presses to argue against it.

Like Helms, Josephus Daniels’s history in the newspaper business stretched back to his childhood. As a teenager, he ran the Cornucopia as an amateur newspaper editor alongside his brother, Charles. Even that early on, it was abundantly clear that Josephus had a gift, and the stomach, for journalism.

By the age of 18, he was editor at the Wilson Advance. Come 1885, he was gifted the Raleigh Farmer and Mechanic newspaper by the legendary ad man, Confederate general, and infamously racist speech-giver Julian Carr. The head of tobacco company Bull Durham’s ad department, Carr amassed a fortune thanks to his cutting-edge marketing techniques—he was rumored to have placed an ad for the tobacco on one of the Great Pyramids of Giza, though that turned out to be more myth than legend.

Even that early on, it was abundantly clear that Josephus had a gift, and the stomach, for journalism.

The only suggestion Carr gave Daniels when he took over the Farmer and Mechanic was that he change the name. He thought that Farmer and Mechanic limited the paper’s potential audience and Daniels agreed; the name was changed to the Raleigh State Chronicle. He ran the paper so successfully that he turned it from a weekly to a daily and, within a year, was offering to take over and buy the state capital’s most established daily, the Raleigh News & Observer, from Samuel Ashe. With a foot in the door of the state’s capital, he methodically put his other foot on the next rung of Raleigh’s social ladder, cozying up to the Democratic legislature, who in return named him the State Printer from 1887-1893.

In 1893, he made his first foray into national politics, when he was named the chief clerk of the Department of the Interior by President Grover Cleveland, entering Daniels into the sphere of federal power where he would remain and through which he would ascend for the rest of his life and career. The following year, with profits soaring and his popularity among the Democrats running high, Daniels finally laid claim to his golden goose—Ashe relented and the N&O was his.

To this point in his career, the politics of Josephus were partially (partially!) admirable, thanks largely to his progressive, anti-industrialist economic ideals, grounded in his humble childhood and experience among the oft-exploited labor force in the state. In his editorials, he challenged railroad businesses attempts to strong-arm the state and its citizenry; he fought for child labor laws; he criticized the Duke family’s outsized influence in the state; and he even vocally supported women’s suffrage.

In 1889, he was made an honorary member of the International Typographical Union, making him the only publisher in the nation to hold the honor. On education, whereas Democrats like John Kilgo (who presently has both a dorm and a parking lot named after him at Duke University) wanted to keep poor citizens out of the university system and strip tax dollars from the K-11 system, Daniels wrote in 1896 that the working class of North Carolina “was too poor not to educate” and called for an increase in education taxes. In 1897, he openly agreed with the Fusionist state legislature’s decision to expand local taxes in the name of education, crossing party lines and writing “the Legislature has done one thing for which credit must be given.”

But those lofty ideals were undercut by Daniels’s lifelong dedication to seeing to it that said government wield hardcore, unrelenting racist tactics against all peoples of color at every turn possible. And by 1898, Daniels had put aside any remaining doubts about the Democratic Party’s top-heavy policies and invested completely in the party line.

This was a man who legitimately believed black people had no innate right to participate in government or society and placed that belief above any other.

He did so because he was a vicious segregationist, and certainly among the most racially conservative power brokers in North Carolina at the turn of the 20th Century. This was a man who legitimately believed black people had no innate right to participate in government or society and placed that belief above any other, often using phrases like “the superior race” to describe white people in his popular editorials.

When Daniels took control of the N&O, the Democratic Party was reeling. Were it not for his death in 1892, Polk—who, despite his position of power, died a poor man after pouring his personal fortune into his fight for working farm families—would have easily been his party’s nominee for president that year. Even so, the Populists and then the Fusionist’s message of class warfare was working.

Farmers flocked to their ranks and the Democrats in the state legislature were forced to inch to the left—the same year as Polk’s death, the Dems passed a a graduated income tax, per Ronnie Faulkner’s North Carolina Democrats and Silver Fusion Politics. But in leaving behind education reform and railroad regulation, the party left behind a great many working class voters.

The answer for Daniels and the Democrats seemed natural: Instead of further capitulating and trying to appease these voters, they wanted to destroy not just the Fusionist Party, but the very base of citizens that put them in power. And in that, they succeeded.

The White Supremacy Campaign of 1898 was as destructive a force as ever touched down in North Carolina.

Daniels, working with Charles Aycock and Furnifold Simmons, began creating what would be deemed the Simmons Machine. The idea, as they saw it, was to gut the Fusionist Party through the one issue they knew could irrevocably sunder an already fraught relationship between the Republicans and Populists—race. Once the partnership was dead, they would aim to construct a one-party system, one in which the Democrats would have complete and total power.

While Aycock and Simmons handled the political rallies and violent insurrections against the black population, Daniels’s role was to push the message onto white North Carolinians, poor and rich, that any alliance made with black citizens was one that would eventually see their coffers drained, their women raped, and their country stolen.

As much as is made of the #FakeNews epidemic ravaging social media, disinformation campaigns are nothing remotely novel or new. And if anyone were in search of a historical template for how one’s position can most effectively be used to disseminate false information, Daniels would serve as an example as good as any.

As much as is made of the #FakeNews epidemic ravaging social media, disinformation campaigns are nothing remotely novel or new.

Daniels spent the entirety of 1898 writing editorials attempting to persuade the Populists to break with the Republicans and join the Democrats, at least at the national level. Marion Butler, a Populist and by all means a supporter of keeping the black citizen in their place, had already reassured voters in 1896 that “there will never be any negro rule” in North Carolina. It was in this rift that Daniels sensed an opportunity.

In the final months of the campaigns, Daniels turned up the heat on a state that was already boiling. On Aug. 18, Alex Manly, publisher of the Wilmington Daily Record and an African-American man, wrote an editorial in his paper that stood strong against the notions being pushed by Daniels, Jennett, and the Democratic establishment. He disavowed the idea that the only relations between white women and black men involved rape, saying that in fact while the white men attempted to “destroy the morality of ours,” there were a great many happy interracial couples and that were it not for the blatant racism consistently displayed, there would be more to follow.

Daniels hurriedly reprinted the column in the N&O, stoking the idiotically primal fears of white men across the state not only by showing that Manly did indeed pen the column in August (per Joseph Morrisson’s Josephus Daniels Says…), but by publishing affidavits to prove just how influential Manly and his Republican cohorts were in Wilmington politics.

To complete the onslaught by election day, Daniels reviewed and approved cartoons drawn by Norman Jennett, many of which opposed what Jennett referred to as “Negro rule,” every single day of the campaign cycle. One cartoon depicted a shoe marked “Negro” stepping on the body of a portly “White Man.” Daniels ran columns in which the abominable illustrations appeared daily from August to Nov. 8, crudely illustrating for their readership the biracial world the Populists hoped to build through the lens of a frightened racist white majority. The tact was gobbled up by the white citizens.

Ballots were stolen and Red Shirts (a KKK-like bunch that stuck around from the terrorist group’s raids during the Reconstruction era) rode across the southeastern part of the state to intimidate potential black voters.

Come Election Day, the Democrats cruised. They claimed 134 seats in the General Assembly, leaving just 30 to Republicans and six to the Populists. But their work was not quite done.

In the days immediately following the Democrats’ sweeping victory in the legislature, Alfred Waddell, a leader of the Red Shirts, called for Manly and his brother to be run out of Wilmington or killed on sight. The resulting uprising—once termed the “Wilmington Race Riot,” and since renamed the “Wilmington Massacre”—ended with at least 60 dead black citizens and the Daily Record’s office in flames. Manning one of the machine guns used to gun down the North Carolinians who dared to stand against the terrorists was William Kenan, Sr., whose name is now being removed from the plaque outside UNC-Chapel Hill’s football stadium.

You know the rest: Jim Crow laws swept through the state and the rest of the South, and by 1900, the idea of a black voter bloc was set to rest, not to be revisited for another half-century. The fragile victories claimed by the Fusionists were dead.

Josephus Daniels, after years of climbing the ladder, had finally pried off the last finger of those attempting to ascend below him. He, and his precious party, had won.

Holding The Line

The easy thing to say—the thing most white people in the South say—is that slavery and Jim Crow were a long time ago and we’re much better now and everyone should stop complaining because nobody alive was a slave or a slave owner.

It is an intensely and infuriatingly stupid sentiment, but its mass appeal—one now sold by Republicans instead of Democrats—is completely understandable.

To have to actively think about how the actions condoned by legislatures 50 years ago might affect, say, how your particular town or city is still segregated or how certain schools tend to take in 80 percent of a county’s minority population, is a taxing prospect. It is much, much easier to put the onus on the communities that were actively legislated against than it is to weigh personal responsibility against societal responsibility, and to contemplate what is embedded in the structure of your governments. And so we are left with the piecemeal deconstruction of Jim Crow and institutionalized racism and sexism that is still dragging on today, right this moment—not because people couldn’t see that their beloved Democratic Party was an oppressive political machine, but because they didn’t, and don’t, want to confront that they and their parents and grandparents actively participated in that same oppression.

So, in the interest of making you think about that, let’s do a quick run through the last 100-odd years in North Carolina politics.

With the Democrats firmly in control of the government at the turn of the 20th century, the table was set for the first 50 years, minus a stray election or two. Furnifold Simmons, who served as U.S. Senator from 1900 to 1930, hand-selected all but one governor during that period. Only William Kitchin, who won the 1908 election, bested the “Simmons machine” candidate; he won on an anti-railroad platform that opposed rate raises, to business owners’ chagrin.

When the Republican Herbert Hoover ran for president against the Catholic New York Democrat Al Smith, Simmons backed Hoover. It was yet another successful attempt to play to the cultural, not ideological, preferences of his Bible Belt state, as Hoover won the state by claiming 55 points to Smith’s 45, making him the first Republican presidential candidate to win in North Carolina since 1872. It somehow worked out for the Democrats when the Great Depression stripped North Carolina’s rural communities bare—the state rejected the Republican Party for another 40 years. North Carolina was, at long last, a one-party system.

But the ruling party, much like the Fusionist Party they destroyed, was not quite as unanimous as it looked. Factions developed within the Democratic party even as it grew to become a member of the Solid South, and conservatives and the progressives fought for power within the party in the coming decades.

The white progressives were only slightly less racist than their counterparts, and supported segregation until it was outlawed. The progressives fought for educating the state’s minority population, and the conservatives fought against it, before finally opting for the classically North Carolinian compromise of allowing a Department of Negro Education to come into being (and then gravely underfunding it for the entirety of its existence.)

The Simmons machine was eventually replaced by the Shelby Dynasty, which similarly dominated state and local elections. Both political machines maintained a strict adherence to “business progressivism,” which meant about what you’d imagine—tax breaks for the rich and lax labor law enforcement highlighting a long campaign to attract industrialists and bankers to the state at the expense of the working class.

The political system wasn’t upended until the election of the rural populist W. Kerr Scott in the 1948 governor’s race. Kerr Scott was a farmer, and his victory marked the first time since the days of the Fusionists that Carolina’s rural voters and common laborers took a successful political stand against the state’s wealthy elite. Kerr Scott also broke with the state’s prevailing political norms by running a campaign that was not based explicitly upon race-based appeals to white voters. In 1949, he appointed the truly liberal UNC-Chapel Hill president Franklin Porter Graham to a Senate seat vacated when Melville Broughton died in-office. A progressive segregationist, Kerr Scott instead spoke against and prosecuted those participating in a resurgent KKK.

But Kerr Scott was opposed by a litany of conservative Democrats, one of the more prominent being a Wake Forest professor named I. Beverly Lake. Many of Lake’s students during the late 1930s went on to fill state-wide court and political positions in the following decades, and the professor himself was a relentless opponent of both Kerr Scott and moderate successors like Luther Hodges.

When Kerr Scott nominated the conservative lawyer Susie Sharp to the state supreme court, Lake opposed it on the basis of her sex. In his 1987 Southern Oral History Project interview, he explained that while he found Sharp a capable colleague, “I’m not personally enthused about women lawyers because to put it somewhat rudely, I guess, I just don’t like to see a sow’s ear made out of a silk purse.”

(Sharp was a complicated one herself. The first female judge in state history, she later became the first female chief justice of the state supreme court; as a conservative, she also opposed the 1975 Equal Rights Amendment, telling the AP in December 1974 that her chief concern was allowing women to be drafted for the military. “I feel like we have the Civil Rights Laws,” she said. “The amendment is not necessary. I think it might deprive women of some legitimate privileges and protections they ought to have.” Helms, along with conservative Senator Sam Ervin, unsuccessfully lobbied for her to be named to the U.S. Supreme Court. After five attempts, the ERA is still not ratified in North Carolina.)

After all those years of regressive, revanchist single-party rule, it looked as if Kerr Scott and the Branchhead Boys, the nickname given to his rural supporters, might actually be able to reform the state and redirect the government’s efforts on helping its poor and maybe even its people of color.

But North Carolina didn’t earn the nickname of the Rip Van Winkle State for nothing, and in 1950 we turned Graham out of office in favor of the intensely racist Willis Smith, thanks in large part to burgeoning media starlet Jesse Helms, who used his position as the leading radio and TV man at WRAL to push Smith over the edge. The race-baiting advertising and press tactics employed by Helms and Smith—recall their “WHITE PEOPLE WAKE UP” spot—were not but a stone’s throw from those of Daniels and Jennett.

As the pendulum swung center to right and then even further to the right over the course of the late-20th century governorships and state legislatures, it was generally done by way of party factions, not parties. The evolution of North Carolina’s Democratic party, and eventually its Republican party, mirrors the evolution of conservatism in America, with each passing politician slowly figuring out how to make the unspeakable steadily more palatable, and eventually something like normal. Helms may not have invented this particular dark art, but from looking to Daniels and his ilk, he mastered it early. Throughout the run of his 30 years in the U.S. Senate, his gift for it never wavered.

And yet, as the conservatives did little more than find a new party to peddle their tricks, the N&O, at speed just a tick above glacial, was changing.

When Jonathan Daniels succeeded Josephus, his father, as editor of the N&O, it marked a stark change in the paper’s politics, a racially progressive turn that largely defines the paper’s relationship with many eastern North Carolinians to this day.

But the seeds sown by the head of the Daniels family—the Southern conservative awakening to the usefulness of inflammatory misinformation campaigns—would see to it that the changes were met with full-throated, and highly effective, opposition.

According to the book Jonathan Daniels and Race Relations, the younger Daniels, one of four sons, was the only one ever to show an interest in becoming an editor. In Raleigh, Jonathan grew up on South Street with black servants. His nanny’s name was Harriet, and a boy named Tucker was hired to basically be his friend and bodyguard. When the state capitol was moved, the Daniels family’s neighborhood changed, resulting in them living next to an African-American family; they also lived down the street from the HBCU Shaw University. As a result, Jonathan was exposed not only to black culture, but also to the basic idea that African-Americans could seek an education and climb the social ladder just like whites, even though access to the upper rungs was restricted by the incredibly racist Jim Crow policies that his father and his cohorts helped implement.

His father’s close ties to FDR further ensured that Jonathan’s was a highly unusual North Carolina childhood. In addition to being the state’s leading newspaper editor, Josephus rose to become Woodrow Wilson’s Secretary of the Navy and was later Roosevelt’s top assistant during FDR’s time in Congress.

When Roosevelt won the presidency, he made Josephus the U.S. Ambassador to Mexico. This meant that instead of coming of age in the heart of North Carolina as his father had, Jonathan spent eight years forming a worldview in the nation’s capital. Jonathan moved to D.C. at the age of 10, and as the son of a Cabinet member, he received a top-flight education and was able to travel across the nation and to Europe. He experienced cultures far outside the southern norms. And like his father before him, he’d grab a spot as a Democratic committeeman; he was even gifted a position as FDR’s press secretary.

The similarities stopped there. Josephus, a staunch Methodist, was likely shocked to know that by the time Jonathan left to attend UNC-Chapel Hill, his son was a committed atheist, a routine chucker of dice, and even a casual drinker. Also unlike his father, Jonathan developed what were then liberal views on race, meaning that when the civil rights movement came along, rather than fleeing the party for the conservative Republicans that sought to revive the state’s Old South values, he supported the campaigns of educators and progressives, such as Frank Graham and Terry Sanford.

In 1937, Jonathan wrote that there was “no general prosperity in the South as long as wages of the black bottom [of the economy] remain in so many cases so pitifully low.” A year later, in an N&O editorial, he opined that “the white people of the South have a great responsibility which they must assume in helping the Negro”

Don’t get me wrong here: Jonathan Daniels was a segregationist and a staunch one-party man. He was a bit nicer about it than his father, though, and notably more touched by the injustices he saw around him. So, with one hand, Jonathan used his editorials to torch the racial iniquities of the criminal justice system—of the 94 people executed in North Carolina between 1909 to 1928, 86 were black—and the other to help maintain Democratic control of the state. Daniels sided with Harry Truman over Dewey and Strom Thormund in the 1948 election, penning editorials on his behalf that argued it was only the Democrats that would give the South any power in Washington.

In doing so, the younger Daniels was creating a growing and new readership base, one that saw the coming decades to include the advances of integration. Simultaneously, he was creating a very real, very raw hatred among the racist and bigoted, the same folks who were growing more and more disillusioned with the direction of the national Democratic Party and any outlets or individuals that would parrot their talking points. That is, the group of people with which Josephus rubbed elbows and was praised by slowly began to despise the N&O. And so, they found themselves new parties and new papers.

For all this, his being more open in his close-mindedness than his father ensured that Helms and his cult of New Republicans would absolutely despise Daniels and the way he ran his paper. It was a hatred that—whether real or performative—Helms would carry with him from the Willis Smith campaign all the way through the 1990s, long after Jonathan had hung up his political cap. (Starting in 1968, Claude Sitton took over as editor of the N&O, marking the first time that a non-Daniels family member was solely running the operation.)

Carter Wrenn, one of Helms’s closest aides for the first 20-odd years of his Senate career, spoke pretty clearly on how Helms, and eventually most of the conservatives who would flee to the Republican Party by the 1980s, came to view N&O and any other mainstream media publications during his SOHP interview:

“They were seen almost as an organ of the Democratic Party, and a powerful one. I can remember elections where we would decide that we really had to run against the News & Observer more than our opponent. That was the perception that I had for years of the News & Observer and the media in general. Conservatives back in the 70s and 80s, and I think still today, sort of have almost a persecution complex when it comes to the media in that they just think that they’re completely alien, hostile to them. My views have changed over the last ten or fifteen years, but that was pretty much the standard view I had and that I think most conservatives and Republicans had in the time I was active in politics, say from the mid-70s to mid-90s.”

And it was this attitude—of other-ing the media, the liberals, the progressives, and any who dared go further left than them—that was adopted by and eventually molded the GOP. If you’re interested in the specific directions charted by both political parties between 1970 and now but haven’t been following along with this series, check these bad boys on the Democrats and Republicans out, and then circle back here. The short of it is that for the past 40 years, the Democrats failed miserably at finding a distinctive platform that resonated with a citizenry that is justifiably distrustful of direct government involvement.

And it was this attitude—of other-ing the media, the liberals, the progressives, and any who dared go further left than them—that was adopted by and eventually molded the GOP.

Meanwhile, the North Carolina GOP latched on to the tactic of aggressively shouting “Nu-uh!” at any sort of criticisms of racism, sexism, homophobia, or xenophobia, all while perfecting a brutally effective outreach model that bypassed the Fourth Estate and instead delivered the filth directly to those that clamored to hear it. Through promoting voices like Helms and Rush Limbaugh through the 1970s and 1980s, they provided a clear-cut identity and thesis statement—one of less government, consolidation, media opposition, and the individual right to consistently fuck one’s self over—and passed legislation that adhered to these standards. In North Carolina, they swept through the state legislature in 2010, took the governorship in 2012, and did (and continue to do), essentially, whatever the hell they wanted. For them, this amounted to providing lower taxes and free handjobs to out-of-state corporations, letting said corporations trash the lands and rivers they inhabited, gutting and resegregating public education, and, again, making it crystal clear that the media is the enemy, not the voice of the people.

What you need to know, both about the state’s voting population and the press that covered it during this time, though, can be summed up as such: The people stayed the same. The only thing that ever changed in North Carolina was the parties.

r/pizzagate, #FakeNews, And Other Depressing Truths

The question presented now is a simple one: Who remains to tell you, the concerned citizen, about all this taxpayer-funded bullshit?

The answer is a bit sobering, at least if you’re not one of the scumbag scam artists trying to make a political career out of blatant grifting. Over the past 20 years, the papers known for being the biggest thorns in the sides of conservatives have slimmed up and consolidated, while locals and alt-weeklies have died off at an appalling rate. The Durham Herald Sun, News & Observer, and Charlotte Observer are all McClatchy papers now, and like a great many dailies, while the quality remains, they’re shells of their former selves in terms of sheer staff size.

With fewer reporters covering a constantly growing population, the news that would once rock communities or the entire state is now left to the few reporters paid for their work, and any failure or misses on their end is a product of a systemic, industry-wide issue. And with news at the tip of one’s fingers—or rather, at the top of one’s timeline—there’s little anyone can do to protect otherwise sane people from conspiracy theories, flat-out lies, or themselves.

This manifests itself in the form of an uninformed electorate. The scariest part now isn’t just that the conservatives claimed power, but that almost nobody in the state even knows the names of their chosen legislative leadership, much to the NCGOP’s benefit: According to an Elon poll published on Feb. 23, 2018, 63 percent of North Carolinians with college degrees know Roy Williams is the UNC men’s basketball coach, and just 15 percent know that Phil Berger rules the Senate or that Tim Moore sits atop the House

Only Republican Commissioner of Labor Cherie Berry has anything close to name recognition among non-governor public servants, and that’s just because Berry put her face in every elevator in the entire state, earning her a weird cult status that completely ignores her support of the state’s ban on collective bargaining by public workers or her serving as a co-char of the state’s Women for Trump chapter or her department’s confirmation that, yes, actually it’s totally fine if your employer fires you because you didn’t show up for a shift in the middle of a hurricane.

63 percent of North Carolinians with college degrees know Roy Williams is the UNC men’s basketball coach, and just 15 percent know that Phil Berger rules the Senate or that Tim Moore sits atop the House.

This is not an indictment of the newspapers that regularly crush their beats covering the state’s hard-right turn. I interned on the sports desk at the N&O in 2015, where through a series of mandatory meetings I thought dull and depressing at the time, I learned that the paper, at that time, was operating in the black and producing some of the best local and state government investigative reporting around, especially on the university front, thanks to intrepid reporters Jane Stancill and Dan Kane. (This is true even when the UNC Board of Trustees actively tries to lock out Stancill and the press so they can talk about their beloved racist statue, Silent Sam, in private.)

Unfortunately, the N&O’s profits were and have regularly been sent elsewhere to pay the debts McClatchy accrued in its other ventures, which has in turn limited the number of higher education, special investigation, and even sports writers the paper can put on any given topic. This came to a head in September 2008, when the N&O was forced to offer buyouts to a staggering 40 percent of its newsroom just two months after firing 70 folks, a move that had been preceded by an initial run of buyouts that April that 33 employees took. If reporters are looking for someone to blame in this particular case, they can rest their woes (and current PR jobs) at the feet of then-McClatchy CEO Gary Pruitt, who thought it a good idea to borrow $2 billion to buy the Knight Ridder paper chain in 2006.

The office, when I was there, was still the same one on South McDowell Street the N&O had been at since Jonathan ran the show. It boasted a two-story printing press, a marvelous relic that I never got to see run. There seemed to be twice as many desks and offices as there were employees (not that it bothered anyone, or at least not that they showed us interns). The pages were still filled every night, and the process in all looked similar to what I imagine it was like in the 1980s and 1990s, plus or minus email.

Of course, the people there now and their peers still carry the yeoman’s load. As the Rob Christensens of the Helms era retire or move on to book-filled semi-retirements, a new generation of reporters has filled their roles. N.C. Insider’s Lauren Horsch and Colin Campbell and the N&O’s Will Doran have staked their claim as the most informative writers on the state legislature beat; WRAL’s Tyler Dukes continues to add to a career built on telling readers where every last penny of their money goes, while co-worker Travis Fain tells them what the donors and politicians are doing with it; Taylor Knopf of NC Health News continues to be one of the best on-the-ground reporters when it comes to, well, North Carolina health news; and NC Policy Watch’s Kris Nordstrom and the N&O’s Keung Hi stand out as the most effective education policy reporters in the state.

But, again, these are largely folks based in or focused on Raleigh, Durham, or Charlotte, and whose work is funded by legacy media outlets. During the same time period when even the looming statewide presences saw drastic cuts, local papers like my hometown one, The Salisbury Post, saw their editions and staff writers shrink to the point that one or two writers and editors are now depended on to prop up entire sections as the papers try to establish a digital presence. In Guilford County, the local papers took yet another hit when Senate Bill 181 passed in the fall of 2017, allowing the county government to bypass the former requirement that public and legal notices be printed in the paper, instead allowing them to post them on their own websites—never mind that nearly 25 percent of Guilford County residents still don’t have internet access.

North Carolina is never and has never been wanting for attention. Be it Amendment One, HB2, or Hurricane Florence, there’s always a flock of national writers waiting to file stories in national magazines and newspapers, stories that are praised for their regional references and light touch on delicate subjects. But like the politics of the state, much of what’s happened across North Carolina requires people outside the urban hubs of Raleigh and Charlotte to pay attention. But to pay attention, you need to be able to pay reporters to tell you what to pay attention to; the sad fact is that adequately funded local journalism is not where the, or any, money’s at right now. If it were, I might well be sitting in a random county commissioners meeting right now.

North Carolina is never and has never been wanting for attention.

The Salisbury Post, boasting a lengthy history that stretches back to 1905, offers a realistic example of what it’s like to follow the news in the 80 small-town and rural counties that populate the state. In August, the Post announced it was cutting its daily print coverage to five days a week. In times of heightened production costs due to federal tariffs and decreasing advertising revenue, the paper is one of hundreds in the state and across the nation that’s been forced to ask its journalists to do more with less. The outlet relies largely on two reporters, Shavonne Walker and Rebecca Rider, to fill their news sections, and just one, Mike London, to handle the county’s sports coverage. Politics—i.e. covering what the hell Carl Ford is up to as the Rowan County representative—is left to Annie Foley, who gets an occasional helping hand from Liz Mooney.

Independent outlets and alt-weeklies like Triad City Beat, the Asheville Blade, and Indy Week all do the Lord’s work in terms trying to fill in the gaps of regional reporting, but, again, there’s not much money to be made, and the issues of production costs and stagnant wages know no bounds. Most recently, this reality was laid bare when the publisher of Creative Loafing, Charlotte’s only alt-weekly, shuttered the publication solely because he wanted to hand his 28-year-old failson a media operation of his own to run into the ground.

All this fits into the larger theme of local newspapers slowly thinning before kicking the bucket—according to an extensive review by the UNC School of Media and Journalism, 1,800 local newspapers have shut their doors since 2004. While digital and print magazine operations like Bitter Southerner and Scalawag have done their best to fill this void, there’s not much money to be made by the freelancers that populate their pages, and their focus is on the South at-large and not solely North Carolina politics. As the UNC study points out, the loss of local papers has hit rural communities the hardest. Per the report, “half of the 3,143 counties in the country now have only one newspaper.” In North Carolina, the losses have been concentrated in the eastern part of the state and in the counties to the southwest of Charlotte.

Again, this is not a condemnation of the people who are tasked with delivering the news in these places; instead, it is a depressing acknowledgment that that the loss of such institutions coinciding with the rise of a political party that has made attacking the press a form of art has left the Tar Heel citizenry at risk of turning to a growing population of bad-faith echo chambers that exist for the sole purpose of indignation and self-confirmation.

On the other side of the tracks, the strain of conservatism that continues to deflate North Carolina’s national reputation has struggled to find any sort of fresh ground to sow.

The conservative mainstays in media have shifted a tad since Helms’s rise, but the message has remained consistent. There’s little in-house criticisms lobbed within the conservative sphere, even in the two years under Trump, as the majority of their efforts have been focused on mudslinging and shouting about socialists, mainly because that pays the bills and gets the “Share” button smashed far more than any logical analysis of the issues or the people promoting them ever will.

WRAL, Helms’s old station, shifted considerably in terms of its editorial stance after longtime owner A.J. Fletcher, a longtime mentor and boss to Helms, died in 1979. While still owned by Capitol Broadcasting Company, it’s outfitted with a team of digital reporters in addition to its news crew and I-Team. It also boasts an editorial board that pens pro-environmentalism opinion pieces and regularly criticizes both Democratic and Republican leadership and even sometimes puts them behind bars. The board is actually regularly lambasted by conservatives, having even been accused of parroting Democratic governor Roy Cooper.

In the institutions and outlets that do exist to further a smoother version of Helms’s policies and ideals there appears to be no innovating whatsoever. Neither the NCGOP or 2018’s conservative media outlets are his direct descendants, but there’s also no way to separate the foundation Helms laid from what’s currently being laid on top of it. In the void left by WRAL’s Viewpoints, nothing substantial has happened in terms of fresh conservative North Carolina voices in media outside of the swamp of radio editorials made nationally popular by Rush Limbaugh during the 1980s and 1990s. And so, instead of any sort of potentially interesting or even intellectually stimulating pervading the pages of the internet, there exists bile and the outlets that solely function as a dirty mop to spread it around while claiming to be part of a solution.

To wit: Although Lady Liberty 1885, run by self-proclaimed former liberal A.P. Dillon, deserves mention too for its incessant string of Democrat-inspired paranoia blogs and tweets, The Daily Haymaker, at least by my reckoning, is at the very least the most authentic of the conservative North Carolina blogs, though capital-r Reasonable Conservatives would guffaw at that observation for fear of association.

The Haymaker is run by Brant Clifton, who worked for Helms in Washington during and right after college. The site claims to pull in 30,000 unique page hits per week—a paltry number in the grand scheme of media, but sometimes it’s not so much how many are reading as who is.

While the NCGOP’s power brokers tend to stay away from actively engaging with the site, the General Assembly’s uber-conservative Republicans, like Cabarrus County House rep Larry Pittman, read and sometime comment. This is a site that links out to Breitbart and Daily Signal on its blogroll sidebar, a site that regularly rips the N&O and called Buzzfeed’s “AM to DM” a “hardcore commie-lib radio show.” (God help them if they ever find Chapo.)

Its posts are poorly written and seem to arrive from a different, darker internet age. On the site you’ll find items like, “Many of us have been doing yeoman’s work beating back the barbarians trying to force the trannies into the ladies room,” or “Sharia law and quite a bit of Islamic teachings are incompatible with The Constitution. These people are devoted to a lot of Dark Ages type practices that typically horrify lefties.”

The takes and art on the subject of immigrants are, well, exactly what you expect:

The Haymaker compared Speciale’s sharing of an objectively racist Obama meme to Democrat Tricia Cotham just tweeting random shit like, “Shrek is just the best.” It regularly refers to N.C. Insider editor Colin Campbell as either “Colon Campbell” or “Gay Stuff !!!™.” (Campbell told me N&O reporters wear their Haymaker insults as “badges of honor.”)

This keeps with the site’s longstanding history of deriding the N&O and individual reporters—back in 2012, Clifton lined up Christensen in his scope. While I’m told nearly every Republican member of the General Assembly at least casually reads the site, there’s not a lot to be taken seriously here. Of course, the editors at quite a few papers said the same about Helms when he was on WRAL.

Now, the Haymaker is despised by basically any and every #NeverTrump conservative polluting a timeline near you, in part because of Clifton’s incessant need to never stop posting, which regularly results in him attacking those same #NeverTrump conservatives anytime they speak ill of the Commander-in-Chief. This results in just the absolute stupidest kind of beef, the kind that only siphons away your brain cells and precious moments on earth.

There are, of course, far more reasonably sounding conservative options on the right. The North State Journal is a statewide outlet that’s mostly straight news mixed in among columns fretting about the national debt. The Civitas Institute has tried a couple times to get something off the ground, but has yet to find a sustainable audience—they currently run a project called Mapping The Left, that exists “to show the magnitude of the radical Left’s infrastructure in North Carolina,” per its About page. All it really does is fret about unions and call out solar energy lobbyists.

The clear establishment leader comes from the John Locke Foundation, the state’s most prominent conservative think tank. It funds the Carolina Journal, a nonprofit publication whose role is to shout about individualism and liberty in a smoother tone than the Haymaker, but with the same intent. John Locke’s chairman of the board, John Hood, is this flaw personified. He’s done a shit job, by comparison, of furthering Helms’s work to warn of the impending Commie invasion—recently, he tried to rail against Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour Party, but ended up fretting about the growing DSA, rolling out a quote from Tony Blair and two from Winston Churchill before closing with a criticism of the Pope.

“How sad and embarrassing that the dominant Western voice of Christianity is blind to the very mechanism that has proved to be the best way to lift humans from poverty and reduce inequality all over the world.”

And this is where it becomes clear that the familiar rhetorical and ideological weapons deployed by Helms are simply being repackaged by North Carolina conservative pundits to this day. When it comes to addressing larger state- and nation-wide political movements, they’re all prone to harping about the left in ways that really seem to purposefully fail to grasp any sort of reasonable, good-faith arguments coming from this side of the tracks and instead flail for the low branch of fear-mongering and generalizing; subsequently, they’re prone to lumping together centrists, liberals, leftists, and progressives in the same “far left” tent and playing off the same FOX News red-baiting that has made many a’folk very rich, or at least halfway famous on North Carolina politics Twitter.

That said, they aren’t the ones you need to worry about, not really.

We have now arrived at the moment where I tell you how depressingly little of everything I just laid out matters to the communities that need to catch up on the news the most.

It’s not the fault of the conservative or progressive or journalistic outlets; they’re all performing their jobs to the best of their abilities on finite budgets, often times exceeding any sort of reasonable expectation. But unless you’re a cave-dwelling nerd with a corporate-funded news accounts (like me), or someone with a decent amount of cash (full digital access N&O runs $134 for the first year) and lots of free time and knowledge of the intricacies that separate news organizations and even specific reporters, then your ability to successfully navigate the news realm is inherently limited, especially given the recent explosion of digital-only outlets and forums that have popped up in the past two decades.

No, the fault lies in large part with Facebook, 4chan, Reddit, Twitter, and literally any other social media outlet where news can be posted and shared without being vetted by a professional—and, more than that, with the people who use them. Remember, if you will, the Bizzaro World wildfire that swept over the heinous parts of the internet that was PizzaGate.

Edgar Welch, a 28-year-old hailing from none other than Salisbury, N.C., carried three days of research into insane child-abuse theories and a loaded AR-15 into Comet Ping Pong on Dec. 4, 2016. His goal was to suss out whether the owner of the Washington D.C. pizzeria was operating a child sex ring in tandem with Hillary Clinton, a theory that was first started on Facebook book by a 60-year-old white lawyer named Cynthia Campbell in the wake of the WikiLeaks release of John Podesta’s hacked emails, per Rolling Stone. The falsehood was subsequently circulated on 4chan, 8chan, Reddit, and Facebook and peddled by Mike Cernovich and Alex Jones on their shows and live-streams; very quickly, it went from a joke to a fully realized attempt at bringing the horrors of Online to the real world, to the point that Reddit even banned their r/Pizzagate forum. But by then, it was too late.

Instead of being donned a national hero and top-notch Man Of Action, Welch found himself firing three rounds from a semi-automatic rifle into a regular pizza parlor filled with parents, children, and a very confused store-owner; shortly later, he stood outside the joint, hands on his head as a police officer took him into custody. Come June 2017, he was sentenced to four years in prison for the spectacle that, by the grace of God, didn’t result in any deaths.

If there’s anything you remember from this story, let it be this: What happened to Welch is completely, entirely normal. His response to it was abnormal and alarming, but he was far from the first person to be so entirely duped by an Internet hoax that he was driven to act or vote on it.

If there’s anything you remember from this story, let it be this: What happened to Welch is completely, entirely normal.

From college football head coaches to your grandparents, the campaigns of mass disinformation are very clearly having a deep, lasting effect on how American people decide to form their thoughts on major issues. North Carolinians and the folks that make up this jagged political system are no different. But these campaigns would not be successful if the same folks had the ability of discernment, one that can only be instilled by spending a great deal of time researching happenings that otherwise have little outright effect on their lives. As people have jobs, kids, bills, health, and a million other stressors to deal with, their engagement with media is limited, and thus when an item comes through their timelines that seems like it could contain even a hint of truth, the act of latching onto that outrage and mashing the share button is now such a purely instinctive habit that the act of discerning between fact and fiction seems to have drifted from the psyches of many good people, if it was ever present.

Allow me to give you a sneak peek at what gets passed around as news among people that can otherwise be described as decent, hard-working North Carolinians. All of these come from people back home I consider to be fine community members, folks who regularly volunteer and give to charity, who I’ve seen lend a hand to someone in need at a moment’s notice. And yet this is the content that is squeezed in between the latest TOO EASY! crockpot recipes and baby photos on my personal Facebook feed on a daily basis:

The above meme brings me to a larger point. The fury generated by watching this phenomenon play out, for me, is two-fold: First is the recognition that none of these people who shared the above posts are wealthy or particularly powerful in their communities. I regularly see posts calling for term limits in Congress, for increased senior and retired citizen care, for an answer to the opioid epidemic that continues to rage in the state, for a completely revamped healthcare system that removes the bottom line from consideration, for a well-funded public school system.

In essence, I see people that know in their bones that the current political institutions at their disposal are inherently corrupt; the problem comes with articulation and the ability to step back from the immediate benefits of, say, slashing the income tax rate and understand what long-term solutions to these issues could actually look like. That’s where the second stage of the fury sets in.

The people we elect to office, in theory, should not be commenting on the Daily Haymaker or participating in #fakenews campaigns that target legitimate news outlets, or mistake bias for falsity. In theory, they should be intelligent and, most of all, trustworthy, at least to the extent that they don’t peddle in active lies just to obtain and retain a seat of power, and they should be the ones to step up and articulate the issues that everyone can see so plainly as holding back entire communities at a time from economic and social progress. Of course, reality flaunts theory nearly every time, at least in this dimension.

The first entry here comes from Phil Berger, the man who has basically run the state’s politics for the past eight years. In 2017, Berger posted a bevy of News & Observer and Charlotte Observer stories on his official Facebook page—the only problem was that he, or one of his staffers, changed the headlines.

- The first went from “Carolinas political leaders react to Trump’s executive order,” to “Cooper flip flops on refugees,” a dig at Democratic governor Roy Cooper. Berger also changed the picture to one of Cooper laughing.

- The second initially read: “In HB2 repeal effort, Gov. Cooper is silent on proposed nondiscrimination law.” Berger’s version read, “Has Roy Cooper flip-flopped on HB 2? Gov. Cooper now refusing to support men in women’s bathrooms.”

- The third read, “Sports official says HB2 closing window on hopes of landing NCAA events.” Berger changed it to, “Cooper’s block of HB2 repeal, unwillingness to compromise is closing window on hopes of landing NCAA events.”

When confronted by executive editor John Drescher, Berger spokeswoman Amy Auth just threw Facebook’s policy back in his face and claimed the website’s guideline to “not use Facebook to do anything unlawful, misleading, malicious, or discriminatory,” didn’t apply to what Berger was attempting to do.

The leader of the North Carolina is not alone. All the way down to the most local levels of North Carolina government, misinformation at the price of being the loudest has seeped its way into popular conservative culture. Below, you can sample a taste of just how little effort is being put into the lies the populate the right—on the left you’ve got state Rep. Michael Speciale; in the top right, Cabarrus County GOP chairman Lanny Lancaster; and in the bottom right, Carolina Cree, head of the Haywood County Board of Elections.

To its immense credit, all of these posts garnered coverage from the N&O. To my depressing, cynical displeasure, I’m not sure just how helpful playing Snopes is for the particular target audiences that already mistakenly categorize the paper and any other outlet deemed part of the Mainstream Media as liars that are just in on the conspiracy. Because that’s what happens—it’s what’s happening right now—in “news deserts,” across the state and nation. Here, where news once thrived in the light of competition among multiple outlets, growing voids of dependable and important local reporting are appearing. And it’s in these voids that agents of misinformation slither their way into the part of the brain that allow humans to discern between falsehood and truth. There, they nestle and cloak themselves in the identity of being part the Us, the group that sees things the way they should be seen; they convince readers and their audience that they are among a community of like-minded people, who believe themselves to share values and ideals. And because there are so many to choose from on social media platforms that refuse to properly vet sourcing or even consider themselves publishers, these bad actors normalize themselves until the line between the two is sproperly muddled and the checks can start being cashed. And the entire damn time—from Josephus Daniels’s white supremacy campaign at the turn of the 20th Century to Jesse Helms’s lifelong crusade against the “librul medya” to r/pizzagate—it has been co-opted by the uber-conservative faction of this state. And now, as papers drop left and right and Facebook and Twitter and Reddit and 4chan and QAnon do nothing but maintain and grow, the fight to slow this ball that’s been rolling for two decades is not slowing; instead, the path is being cleared and buttered by the same folks who have always done it.

It’s not a surprise, it’s not a mystery, it is, simply, the result of history bleeding into the present. But I do not know where we go from here.

Parting Thoughts

The point of this series was never to for me to end with some grand rant about What This Means.

I have no clue what to make of all this, not in terms of providing a clear solution to the myriad of issues at-hand. What I know is exactly what you probably know, whether you admit it to yourself and others or not.

The GOP is infested with xenophobic, sexist, racist shitheads because they are the ones that have consistently charted the course of the party the past 60 years, and they annoyingly share the room with a depressing number of Never-Trump boys that make a living yelling at you not to paint them with a broad brush. The Democratic Party is void of a single backbone or clear thesis on what the hell it stands for, but it has plenty of grifters to go around. The news media is dwindling and forcing talented reporters to choose between paying bills and pursuing their passion. Social media is a fucking mess that should probably be scalded from existence at the least, but instead seems to be the only constantly growing outlet in the hellscape that is the media industry. There are no clear answers as to how an informed and engaged citizenry could do anything, and no answers as to how the citizenry we have could become so.

The South, and North Carolina in particular, is whatever you want to make it out to be. If you lean to the right, you’re seeing your dreams come to fruition but recognize they’re built on shaky ground and shady characters. If you lean toward the middle-left, you’re holding your breath for a blue wave that will do little more than prevent the Republicans from passing the most heinous of their legislative measures. If you lean a bit further to the left, you’re disgusted at the ground Democrats have ceded time and time again, and you’re also probably gullible for thinking any sort of semi-socialist measures will be implemented in your home state in the next half-century in response to Trumpian politics.

And yet—and yet—North Carolina, to me and I’m sure some others, is still the greatest state in this union. Not because of all this shit, but because of how many glimpses it’s provided me and others of what it could be. This is, after all, the state that raised Pauli Murray; it’s the state that gave us Crystal Lee Sutton aka the real-life, bad-ass Norma Rae; it’s the state that said to hell with the Establishment and pushed Kerr Scott and the people of the fields, my people, out of the fields and into a once-real middle class.

There are also very real regressions, ones people choose to ignore or embrace as a return to the good ol’ days when in fact they are being dragged down to the sea floor, just a little slower. But there are victories, here, that are worth looking at every bit as much as the abject failure of the institutional power structures to cultivate more of those scrappy fighters we claim as forgotten heroes.

And so, I will continue to write and cover and unearth all I can about North Carolina, not because the state needs it—there are plenty of talented North Carolinian writers to go around—but because I need it, because I need to know that the last eight years, however bad they’ve been, do not wholly define a state whose contradictions exist in part to show those that have ever called it home the possibilities of what a great Southern state can really be. I don’t expect wholesale change. Hell, I don’t expect much change at all for at least a decade. But if this state has shown the nation anything, it’s that change can come if the right people are provided the keys to power.

And the existence of such a possibility, for now, will have to do.