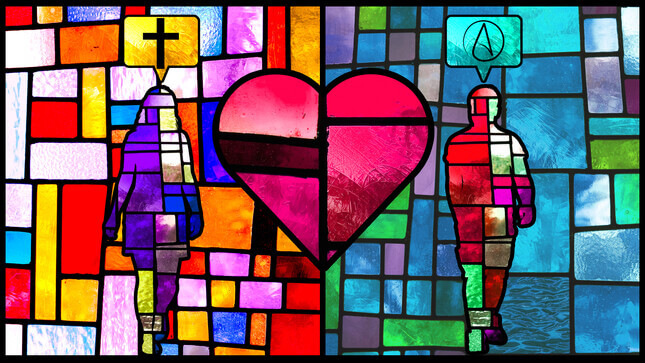

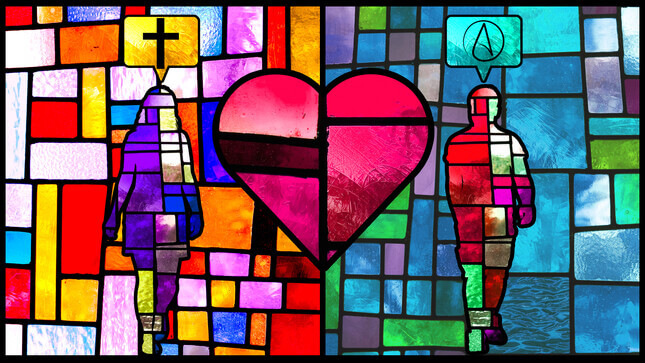

What Happens When the Daughter of a Priest and a Nun Falls in Love With an Atheist?

Features

Soul Searching is our series about how the most secular generation in history is changing the face of religion.

On our second date, my now-boyfriend and I wandered down the chaparral-studded hillside from the Getty Museum in L.A.’s summer twilight. As we kept an eye out for mountain lions, he told me he was divorced.

In response, I shared a disclosure of my own: that when my parents met and fell in love, my mother was a former nun and my father was still a priest. After having left the convent hoping to get married, my mother had nearly given up on meeting someone—until she met my dad over breakfast with a mutual priest friend. My dad walked her to her car, and they stood talking for five hours. When she got home, she called a friend to say she’d met the man she was going to marry.

That said, my parents initially tried to resist the attraction, at least for a while. My mom even considered moving, because she didn’t want to take my dad away from his vows. But eventually they decided to get married and start a family, compelling my father to leave the priesthood. Their families came around, but the scandal cost them several friends (some of whom later left religious life themselves to get married).

I love the drama and romance of this story, but detailing my family history that night, mere hours into a new relationship, felt fraught with risk. I already knew from Jeff’s online profile that he wasn’t religious. How would he feel about dating a girl from a super-Catholic family? Even though my life today looks largely secular, my parents’ history remains important to me. I was protective of it.

Jeff received my revelation patiently, though he later told me he thought it was odd the way my story bore a tinge of confession. Our second date soon led to our third, fourth and 25th. But my compatibility fears weren’t unfounded. His background could hardly have diverged more from mine, religiously speaking: His father spent his career in aerospace, and his mother was a science teacher. Like Jeff, they remain confirmed atheists.

I, on the other hand, grew up attending weekly mass with my parents and sister and debating women’s ordination and social justice over the dinner table. We were the kind of family that critiqued the priest’s homily on the drive home from church. When my parents wanted to annoy me and my sister, or when they got swept up in a fit of nostalgia, they’d break into Latin hymns.

I’ve agonized about moving forward until Jeff and I resolve this bedrock issue. Anxiety over our faith differences has woken me from sleep with a bolt of panic—“Am I kidding myself that we can make this work?”

Where I saw a sweet, harmless tradition, Jeff saw creepy indoctrination of young minds.

Our mismatched relationship, though extreme, isn’t unusual nowadays. Among couples married since 2010, almost four in 10 have a spouse from a different religious tradition, according to a study by the Pew Research Center. And among couples who live together, as Jeff and I do, almost half are mixed-faith unions.

Among young people, the portion of religious “nones” is more than one third, the highest of any generation. When I’ve told older people about Jeff’s and my religious backgrounds, they look concerned. “You’re going to have fun when it’s time to have kids,” one woman, herself raised Catholic and now divorced from an atheist, told me recently.

But I’ve also dated Catholics, and discovered that my particular brand of Catholic upbringing—relatively liberal, intellectually questioning, irreverent—wasn’t everybody’s. In some ways, it’s easier dating someone who doesn’t bring his own body of personal experience to my religious tradition. If our generation doesn’t want to be confined to a narrow band of “suitable” same-faith partners, more of us will find ourselves in these bridge couplings, navigating the challenges that come with them.

Most of the time, Jeff’s and my differences aren’t a big deal. But occasionally, we’ll butt heads, like when he joins me for Christmas and Easter services with my family. At the most recent Midnight Mass, our pastor gathered sleepy kids around the manger to answer questions about the nativity story. In eager lisps they named farm animals and explained how Christmas celebrated the birth of Jesus. Where I saw a sweet, harmless tradition, Jeff saw creepy indoctrination of young minds.

My parents are now marriage and family therapists, and when my sister and I were growing up they encouraged us to marry partners of a similar faith background—partly because they so often counseled interfaith couples who couldn’t agree on how to raise their kids.

Jeff and I have been together almost four years now, and we’ve discussed getting married many times. But negotiating the religious identity of our hypothetical offspring has proved a sticking point. I’ve struggled for years to answer a simple question: How important, exactly, is all this to me?

Like many people, I started having serious doubts about the Church around the time of the sex abuse scandal in the early 2000s, but I didn’t start moving away from it until after college. At the time, still living at home and navigating post-grad life, I couldn’t bear to fill the role of the dutiful daughter accompanying my parents to church every Sunday. That was gradually compounded by other concerns like the Church’s official position on homosexuality, its complicated relationship with women, and the ongoing failure to address the sex abuse crisis. As I moved into more and more secular circles, I started wondering at what point I would stop defending an institution that now required me to make so many excuses for it.

At the same time, Catholic spirituality is the language of my childhood and my family. Forsaking it feels gutless, and perhaps short-sighted. Even though I don’t feel the need to attend church regularly now, I don’t know how that desire might change once Jeff and I have kids. How will I feel skipping the Catholic sacraments that were rites of passage for me and my friends, that gave me a sense of self and belonging in our church?

During one of our worst fights, he said that if I decided I could only be happy raising our kids 100% Catholic, we were going to have a problem.

For the first couple of years after Jeff and I started dating, we had long talks over glasses of whiskey debating these issues. But we never came to a resolution. Studies show that in most mixed-faith families with a “none,” the more devout partner—usually the mother—takes the lead on the kids’ religious upbringing. But Jeff doesn’t want to outsource his children’s spiritual development to me and the Catholic Church every Sunday. He wants to be an active participant, and he says he’ll never feel truly welcome in an environment built around a faith he doesn’t share. He doesn’t want to fake it. His integrity and paternal instincts are partly why I love him—but they also make reaching a solution a pain in the ass.

We started church-shopping with the Unitarian Universalists, who define themselves by principles like respect for others, the environment, and a commitment to social justice. The thinking was that here, we could meet on neutral ground.

But though the people we met welcomed us, the hodgepodge of beliefs and exotic services gave me a pang for the liturgies of my childhood. Without a specific God to discuss, the sermons veered toward anti-Trump harangues and liberal talking points. With the 2016 election raging outside, I longed for church to serve as a refuge.

Though he shared my disappointment in the partisan pulpit, these complaints annoyed Jeff. For him, even Unitarianism was a huge concession to organized religion, and he felt frustrated that I didn’t seem to appreciate that. During one of our worst fights, he said that if I decided I could only be happy raising our kids 100% Catholic, we were going to have a problem. It was an emotional breaking point that left us skirting the issue for months afterward.

I’ve thought of the cedar chest at the foot of my parents’ bed, the one that holds the baptismal gown my mother and her siblings wore, and that she then used for me and my sister. I don’t know if my kids will wear it. I’ll never be able to match the life experience and spirituality that nourished my parents’ marriage and our family identity.

But despite our differences, Jeff and I want the same things for our kids—for them to engage with the world as curious, articulate, critical thinkers; to feel joy, transcendence and wonder at the world; to develop into compassionate, respectful and open-minded people. And we want them to be conversant with faith, rather than seeing it as something to be mocked or ridiculed.

It might have been more convenient to fall in love with a man who shared my faith background, but it didn’t work out that way. That’s OK—my parents didn’t fall in love according to plan, either.